An Antarctic meeting in Ireland

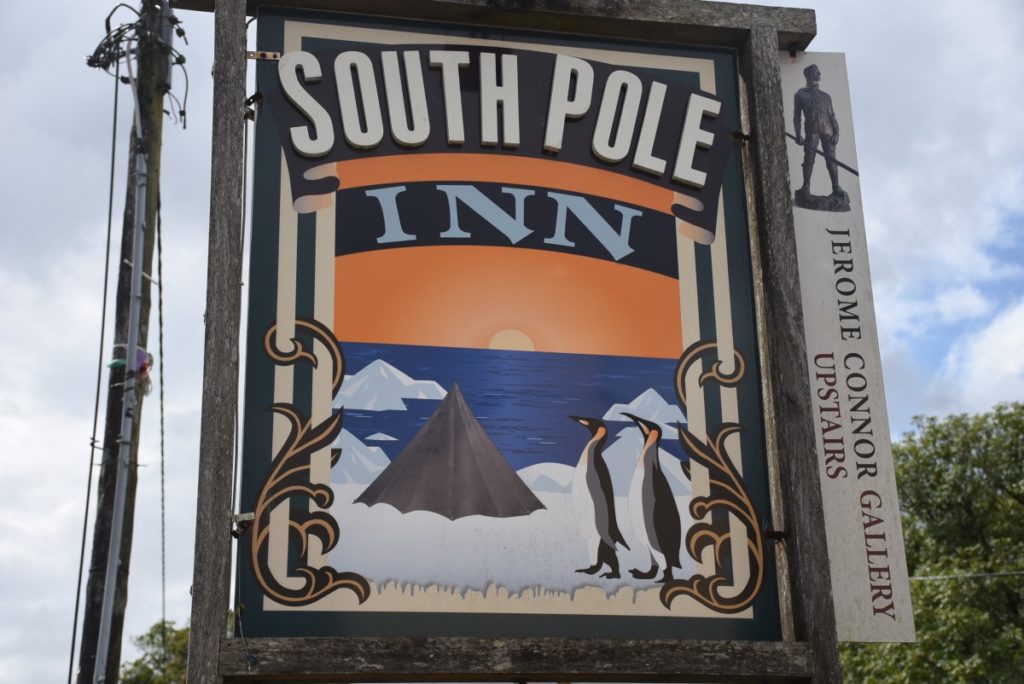

During a cycling trek along the Wild Atlantic Way, a stop at the South Pole Inn leads to a discovery

by Kevin Vallely

“You’ve been here before?” asks the man at the picnic table in front.

“Third time,” I say. “Tom Crean’s a hero of mine. This is my third time here to the South Pole pub.”

“Hero?! Why’s that?” he asks, a little perplexed. “You’re an American, aren’t you!? How’d you hear of Tom Crean?”

“I’m Canadian actually,” I say, “But my folks are from Ireland…Limerick. I skied to the South Pole in 2009. Three-man Canadian team. I’ve always felt a really strong connection to the guy. I love coming here.”

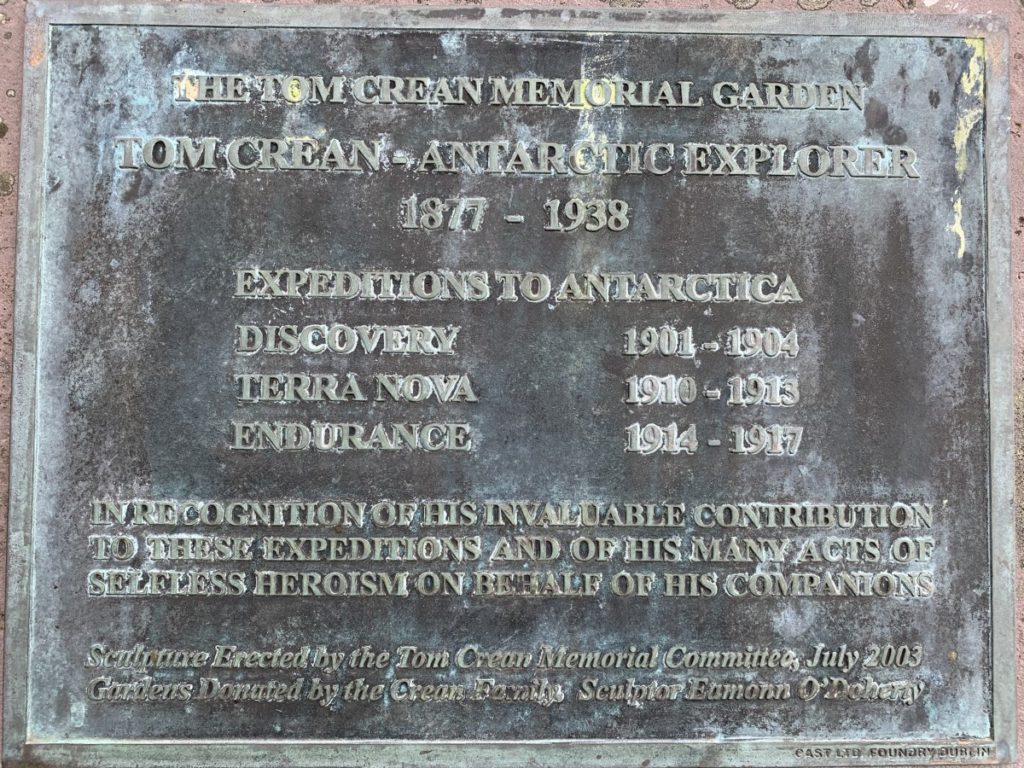

Tom Crean was a critical player in the so-called Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration and has become an iconic figure in Irish history. Crean started his career by enlisting in the British Royal Navy in 1893 at the age of 15. This was a time when Ireland was still under British rule and, little doubt, the mystique of an adventurous life at sea drew the young man. In 1901 he volunteered to be part of Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery Expedition to Antarctica. During this 1901-1904 research expedition, Crean proved himself a physical beast of a man with an even temper that resulted him being asked aboard Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition in 1910-13. On this expedition, Scott made his bid for the South Pole using support parties to cash equipment and food along the route for the journey back. Crean was part of the final group of eight men who marched on the polar plateau, but was not chosen by Scott to join the final party of five to make the polar bid. Crean and the two other men returned to base camp. They barely made it back. Scott and team never would and would freeze to death on their return journey.

Again, because of his exemplary service on his previous two expeditions, Crean was asked to be part of Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance Expedition in 1914-1917. During this infamous voyage, the ship, the Endurance, became beset in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea in 1915, was crushed and sunk. The men then needed to make a perilous escape by lifeboat to Elephant Island where Crean and a handful of men were selected to attempt the 800 nautical mile journey to South Georgia in a rowboat. This 17-day journey, across one of the most ferocious bodies of water on the planet, is considered one of the most astonishing feats of seamanship in recorded history. Upon reaching South Georgia, Shackleton chose the two strongest men – Crean and Worsley – to join him on the trek over the glaciers and mountains of the island to the opposite shore to the nearest manned whaling station. In the end, not a single crew member would perish from the expedition. Crean would prove himself a critical player in the greatest polar expeditions of our time.

“I’ve been aware of Crean well before I skied to the pole.” I said. “I even took his book on my expedition to the Northwest Passage in 2013.”

“Fancy that!” says the man at the picnic table, “I’m the publisher of that book!”

And so began a long conversation between two polar junkies in the lush green valley of Annuscoal, Ireland.

“If you cycle a couple miles up the road there,” points my newfound friend to a road on the opposite side of the river, “you’ll come to the graveyard where he’s buried. It’s well worth the effort.”

And it’s an effort we make. I may be as far-removed from Antarctica as one could be on this planet, but standing at the gravesite of my polar hero, I feel connected to that place in a way I could never have imagined.

Part 1: Two Canadian families set off into the unknown on an Irish cycling journey

Part 2: The ups and downs of Ireland’s west coast

Part 3: The wild Atlantic weather rears its head on Ireland’s west coast

Part 4: Weather adds a new dimension to the challenge of bike packing with kids on the Wild Atlantic Way

Part 5: Pool noodles on the Wild Atlantic Way

Part 6: Punctures and friendly locals on the Wild Atlantic Way