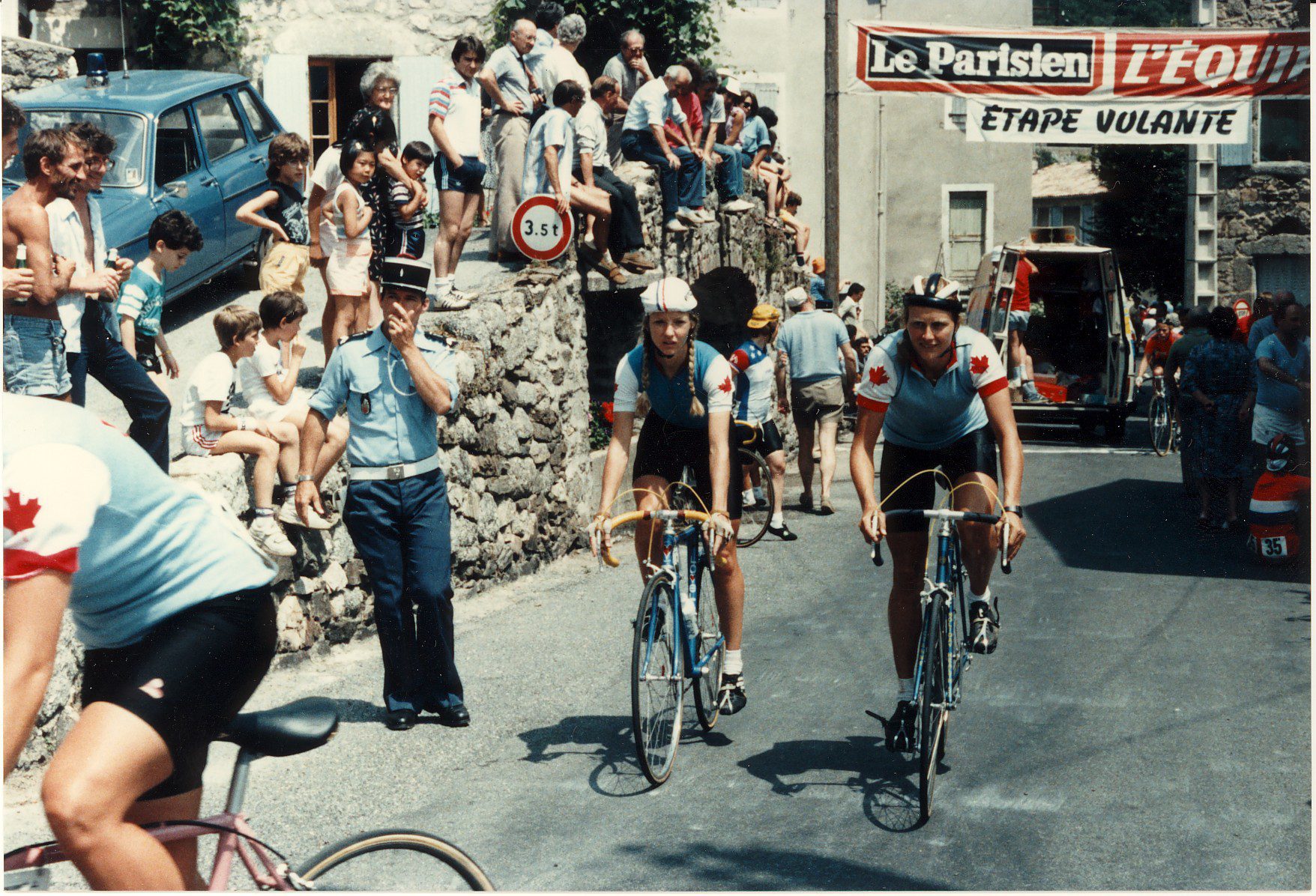

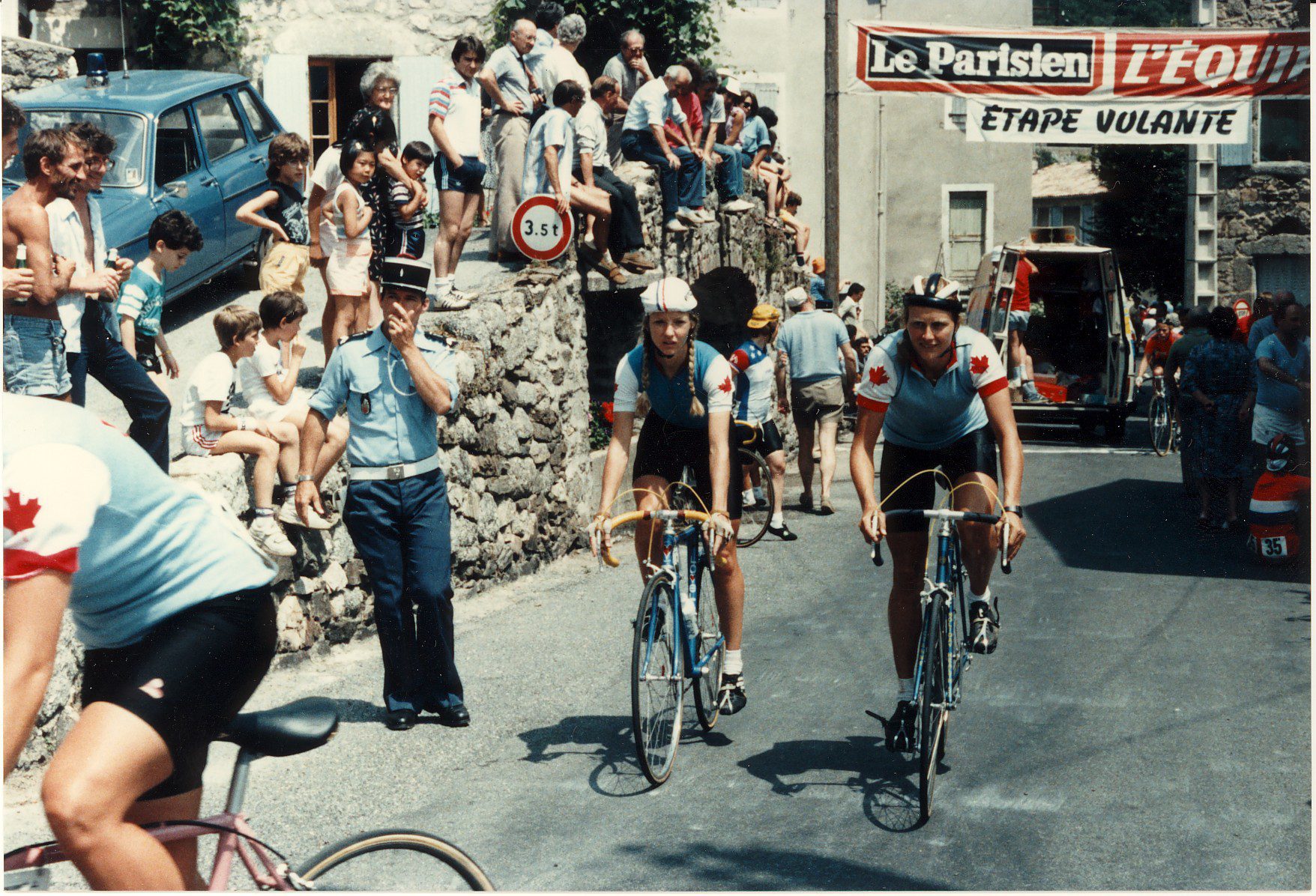

The six Canadian riders who made history at the Tour de France Feminin

Milestones from 1984 are almost forgotten

Photo by:

Marilyn Trout

Photo by:

Marilyn Trout

If you think of the greatest accomplishments in Canadian cycling history, the names Lovell, Bauer, Sydor, Hesjedal and Pendrel are probably the first to come to mind. But in the summer of 1984, a group of Canadian women who had never raced together as a team arrived in Paris wide-eyed and full of optimism to compete in the first Tour de France Féminin since 1955.

By the race organizers, the athletes were treated like queens: they were put up in nice hotels and provided delicious food. By the media, the women were treated more like outcasts. Pundits seemed to believe that the delicate feminine bodies couldn’t possibly handle what was about to hit them. “I have absolutely nothing against women’s sports, but cycling is much too difficult for a woman,” five-time Tour winner Jacques Anquetil wrote in a piece for L’Equipe at the time. “They are not made for the sport. I prefer to see a woman in a short white skirt, not racing shorts.”

And by the fans—especially the hundreds of thousands of women who came out to see history being made—they were a sideshow that stole the spotlight. “It was the beginning of a new generation of women’s cycling,” says Kelly-Ann Way, who was one of the most experienced riders on Canada’s six-woman squad at the race. Way’s name rarely cracks the lists of top Canadian cycling achievements, and yet what she did on July 8, 1984 was a key moment not only for women in cycling, but proved that North Americans of both genders had the talent to compete in the world’s biggest races.

“My husband is a former cyclist as well, and he said, ‘If you were a man, you’d have lots of money,’ There were men who accomplished a quarter of what I did and ” Way trails off, clearly reflecting on the what-if. “You can be bitter about it. But, what can I do? I was just pleased that I was able to push myself to race at that level. I know what I accomplished, and no one can take that away.”

What Way accomplished alongside her five Team Canada colleagues was not only finishing the 18-stage 1984 Women’s Tour de France, but becoming the first-ever non-European to win a stage of either the men’s or women’s Tour—not that you can find that information easily online. “It doesn’t surprise me, but I find it sad,” Way says about the lack of recognition for Team Canada’s accomplishments. “It’s a piece of history of what women athletes accomplished, despite a lack of support and no funding.”

Stage 8 in the 1984 Women’s Tour was a 70-km journey from Aire-sur-l’Adour south to Pau. Up until that sunny Sunday, the race had been utterly dominated by the Dutch. The field was made up of two French teams, one U.S. squad, one British, the Canadians and the powerful group from the Netherlands. In the first week, the Dutch women won every single stage and had at least three riders in the top five in all but one stage.

But the diverse group of Canadians were never far back. While a podium eluded them in that first week, Marilyn Wells (now Marilyn Trout), a 23-year-old rider from St. Catharines, Ont., finished fifth on Stage 5 from L’Aigle to Alençon. After a rest day (the women were only permitted to race 18 stages compared with the men’s 23), Vancouver’s Suzanne Lemieux bettered Wells’ result with a fourth-place finish on Stage 6 from Condé to Nantes. “I think we were all getting tired of getting beaten by the Dutch,” Way says.

In a meeting before the 70-km Stage 8, Way told her teammates that with the race heading farther south into the foothills of the French Alps, it was the day a win was possible. “The Dutch women were very good sprinters, and because women’s racing was so big in Holland, they were used to racing as a team. They had it down to an art,” she says. “But the Stage 8 terrain was full of rolling hills, which was more conducive to me. I think it snapped the Dutch ladies’ legs a little bit.”

The plan was to attack repeatedly. The Canadians and other teams would send riders up the road over and over until something stuck or the Dutch ran out of women to cover the efforts. The two-hour stage was a furious battle. After numerous breaks failed, a group of seven riders went off the front with about 10 km to go, and it stuck. Most of the five countries competing were represented and many of the race’s top riders were present.

“We were pretty gung-ho that day,” Way says. “Hilary Matte and I were in the breakaway and with 1 km to go, I attacked. I knew it would be long enough that I would snap the legs of any sprinter who went with me.” Nobody was able to stick with Way. She crossed the finish line ahead of the Netherland’s Helene Hage, American Marianne Martin, who would go on to win the Tour, and her Canadian teammate Matte in fourth.

Way remembers the walls of people at the finish line in Pau. “One of the biggest fears the organizers had was that people wouldn’t be interested. But they had a new type of spectator out and it was the women,” she says. “I remember vividly all of these university-age girls waving signs and screaming.”

They weren’t the only ones screaming.

Matte (now Hilary Brown), who had played a major supporting role that day and throughout the Tour, was elated to see her teammate take the stage. “I was really happy we won and that we executed a plan that worked,” says Matte.

Way recalls her teammate riding up beside her after the finish line yelling that the top of her lungs, “Gagné! Gagné!”

The Canadian victory had finally ended the Dutch winning streak. Way says the Netherlands’ coach walked up to Canadian directeur sportif Michel Banos, shook his hand and said, “Thank God. I’m tired of hearing my riders bicker about who would win each day.”

But more than a moment of relief for Banos, it was an historic win. It was the first time a non-European, male or female, had won a stage of the Tour de France. It was finally enough to get the Tour some recognition in North America, with Way and the Canadians landing an interview on CBC later that night.

It was an incredible juxtaposition from two weeks earlier, when the Canadian women were racing on the backroads of Ontario’s Niagara region, trying to land a spot on the Olympic team for the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles. That’s right, racing in the first-ever Women’s Tour de France was actually a consolation prize.

The five-stage Niagara Classic in late June served as the 1984 Olympic trials. More than three decades later, there’s still some confusion over exactly what riders were told pre-race about who would go to Los Angeles and who would be sent to France, but the general understanding was that the top finishers overall would end up in one of the two races. “To this day, I don’t know what their selection criteria were,” says Way. “If you talk to 10 different people, you’ll get 10 different stories.”

As the race concluded, there was some controversy when two of Canada’s top riders at the time, including the legendary Karen Strong and the reigning Canadian road racing champion, Marie-Claude Audet, didn’t finish. Strong had been hit with the flu and didn’t start the fifth stage, and Audet had crashed out of that final stage.

“On the Sunday night after the final stage, they announced who was going to the Olympics and who was going to the Tour,” Wells says, recalling some tension in the room when it was announced that Audet and Strong were both going to the Games, along with Niagara Classic overall winner, Geneviève Robic-Brunet.

Matte thinks riders were told before the Classic that the top four were going to the Olympics, but Way, who finished second overall, was sent to the Tour instead. “I should have gone to the Olympics, but there seemed to be a lot of confusion, and they kept changing the criteria. I was going and then I wasn’t, and so off to the Tour I went,” Way says.

Adds Matte, “The best went to the Olympics, and we were the B riders.”

Way eventually competed in the 1988 Olympic road race and both the road and track events at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, but she can’t help but wonder would could have been. “I would have loved for my mom to see me in the Olympics, and you always question what you could have done,” says Way, whose mother passed away in 1986. “You can’t hold on to that stuff because you’d just grow up to be a bitter person. Everything has a purpose. Maybe I needed that Tour de France in 1984 as a confidence booster to say I can perform on the international level.”

While the Canadian team of Way, Wells, Matte, Lemieux, Jacqueline Shaw and Senta Bauermeister that left for France four days after completing the Niagara Classic was hardly a cohesive unit, its members were all aware that they were part of something special. The women had to cover most of their travel expenses to get to France and supply their own bikes and spare parts. They wore their own bib shorts and were each given one single Team Canada jersey to race in. “It had to be given back at the end of the Tour,” Matte says with a laugh. But somehow it was all worth it.

“Nothing bothered us,” Wells says. “It was just so exciting to go to the Tour de France.” While treatment by the French media was awful, Wells says race organizers treated the riders like royalty. “We were treated like queens,” she says. “We were just thrilled that we got put up in a hotel and got fed. It was unheard of for a women’s race.”

After 18 stages and 1,067 km, all six Canadian women and all but one of the 36 riders who started that first-ever Women’s Tour de France rode onto the Champs-Élysées and across the finish line. “When you go around that route, you see the Arc de Triomphe you think, I’m in a movie. It was pretty phenomenal. That never leaves you,” says Wells. “I watch the Tour every year, and it never gets old. It takes you right back.”

In the end, it wasn’t the Dutch who claimed victory, but the U.S. rider Martin, who also made history by becoming the first non-European to win the overall title. Behind her, Wells was eighth, Lemieux 12th, Matte 14th, Way 20th, Bauermeister 22nd and Shaw 29th.

The six Canadians came home and went their separate ways. Some went on to accomplish even bigger things on the bike, such as Way, who rode in two Olympics and three more Women’s Tours—briefly wearing the yellow jersey during the 1989 edition.

Following the 1984 Tour, the Canadian riders were highly respected—locally at least—for what they had been able to do. “When I had first joined a cycling club, I wasn’t really welcome as a female,” says Matte. “But all of these riders I rode with were so focused on the Tour. So, when I raced in it and did well, I came home and was totally accepted after that.”

In 1982, Matte had became the first Canadian woman to finish an Ironman, and she went on to finish four more throughout the 1980s, but still considers the Tour de France Féminin the pinnacle of her athletic career. “That’s the race I’m most proud of because we were the first women to ride it, because we won a stage and because of the small role I played,” she says.

For Wells, the 1984 race was about more than the order of names on a results sheet. “We were guinea pigs. I remember one quote saying, ‘These women won’t get to the finish without a casualty. It’s not made for women. Someone will probably die,'” she says. “We were there representing something bigger than ourselves.”

Despite the historic nature of the accomplishment, little information can be found about that first race, especially in Canada, where the achievements of the six riders from across the country who did something no other non-Europeans had ever done is rarely mentioned. “We didn’t do it for the praise, but it’s not even in the history books,” Wells says. “It was never showcased, and it gets smaller and smaller as time goes on.”

But it’s hard to argue the role their involvement played in opening doors for future generations of women in cycling. Wells calls it a stepping stone for where women’s cycling is today. Way says they were pioneers for riders such as Clara Hughes. “It just validated us as athletes and showed that if you throw something at us, we can do it,” Way says. “We were just happy to have a stage race in a theatre like the Tour de France.”