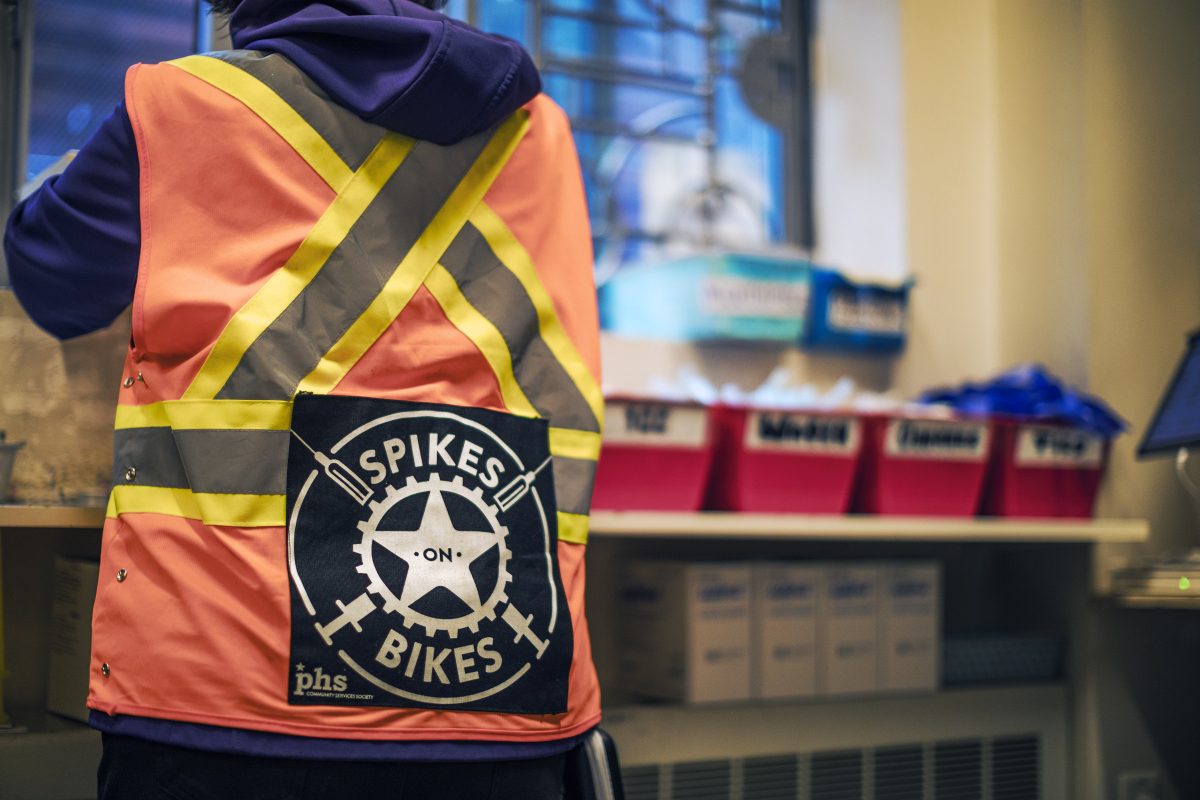

Spikes on Bikes is helping those in the midst of the opioid crisis

Since 2016, the harm-reduction program based in the Vancouver's Downtown Eastside has benefited both those struggling with addiction and those trying to help

by Tom Babin

One night a few months into his new job riding a bike through Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside looking for lives to save, Randy Pandora came upon a man sitting between two Dumpsters. Most passersby wouldn’t have noticed, but here, in the midst of a national opioid crisis, Pandora, who has worked for 15 years helping the homeless and drug-addicted in this neighbourhood, saw danger. If the man was suffering from a drug overdose, he was moments from falling between the Dumpsters where he would be invisible to the street as his breathing would slow until it stopped completely. It would be a lonely death in a place where such deaths are heartbreakingly common. Pandora pedalled directly to the man and leaned in to investigate. It was an overdose. Pandora also realized the man was an old friend.

Pandora, a tall man with a hunch and a limp, recounted this story while dressed in a dapper newsboy cap as he walked with me down East Hastings Street, the notorious boulevard in Vancouver that has become synonymous with Canada’s callous treatment of drug addiction, and ground zero for the country’s opioid crisis. As we walk, he nods at friends and acquaintances passing by.

Pandora, an artist who describes himself as an “occasional drug user” and who speaks with a gravelly worldliness borne of familiarity with these streets, works with PHS Community Services Society on harm-reduction strategies, an approach to treating drug addiction that focuses on health rather than law enforcement. For years, this meant handing out clean needles and encouraging healthy lives. But when the opioid crisis hit Vancouver—and everybody here has no doubt it’s a crisis—new needs arose. A little more than two years ago, the number of overdoses on the streets grew. There were also more calls to remove used needles from streets and parks. People in need of help were turning up more often in more places. To address these growing problems, PHS needed a program that could get help into the community more quickly and nimbly than its existing services. The result was Spikes on Bikes.

The plan was to use bicycles to get aid workers into the community more quickly and deeply than is possible in a motor vehicle. But something unexpected happened. The bicycle did more than just get help onto the streets more efficiently. It opened up new avenues to those in need, became a symbol of community and acceptance and, most important, delivered purpose and focus, not just to those receiving aid, but to those riding the bikes, too. In a place where high-minded talk of hope tends to get worn down by the day-to-day realities of pain, trauma, overdoses and politics, the bike has forged a path forward.

A few blocks east of tourists taking selfies in front of Vancouver’s famous steam clock, the rustic tourist trappings of Gastown abruptly give way to the Downtown Eastside. Here, down an alley of litter and a damp smell of humanity, is a dispensary window, where a lineup of people has formed at 9 a.m. on a Friday morning to pick up clean needles. I’m behind that window, in the office of PHS, an organization that has been working in this neighborhood for years to help its residents. It’s an organized but packed space where floor-to-ceiling shelves hold boxes of medical supplies, and a bustle of activity blends young social workers from middle-class neighbourhoods with aged-before-their-time residents of the street. It’s about as far from the image of Gastown as you can get, a dichotomy not lost on my host, Sarah Whidden, who gave up a comfortable corporate gig at the nearby office of Lululemon to work here.

The opioid crisis has infiltrated all parts of Canadian society. Overdose deaths killed nearly 4,000 Canadians in 2017, according to Canada’s chief public health officer Dr. Theresa Tam, in her annual report on the state of public health. “This is the most significant public-health crisis that we’ve seen for many decades,” Tam told CBC News. But this neighbourhood remains—stubbornly, probably unfairly—the image of the crisis for many Canadians. The area is also at the forefront of harm reduction in Canada, the place where the country’s first safe-injection site opened, and the neighbourhood where PHS operates with a simple focus: keep people alive.

Part of what makes programs here work, Whidden says, is people like Pandora. PHS often employs “peers” to execute its harm-reduction strategies, meaning people who aren’t far from the street themselves—former and recovering drug addicts, the homeless and others with connections to this neighbourhood. “There are a lot of people hurting down here,” Pandora says. “We do what we can.”

As such, it was the peers who were among those who felt the first waves of North America’s opioid crisis. According to statistics from the BC Emergency Health Service, Vancouver emergency services was called for an average of 49 overdose calls per month in the Downtown Eastside in early 2016. By November of that year, it had reached 262. That number has fallen slightly from that peak, but remains high.

In the midst of this, PHS workers realized they needed a way to move throughout the neighbourhood quickly to complete the mundane tasks of harm reduction, such as cleaning up needle sites, educating residents and handing out kits of lifesaving naloxone to those who too often see their cohorts dying. Into this process came a machine that was already on its way to becoming a symbol of the city: the bicycle. Driven by a bike-friendly mayor and a flurry of new bike lanes, Vancouver was in the midst of a bike boom that saw the bicycle driving itself into the consciousness of the city and, more practically, showing that getting around on two wheels was faster, easier and cheaper than other transportation modes, which didn’t go unnoticed over at PHS.

In late 2016, workers got a handful of refurbished workhorse bikes, then installed baskets and racks loaded with pamphlets, clean needles and latex gloves. After peers got a few hours of training in safe cycling and the rules of the road, Spikes on Bikes was off.

Pandora was among the first group of workers on bikes under the Spikes on Bikes program. He quickly realized the program was capable of more than just responding to dirty-needle complaints. On a bike, he was able to cover more ground and meet more people, distributing information about free meals, shelters, safe-injection sites and healthy habits. There are more direct benefits to the program, as well.

Spikes on Bikes sees pairs of cyclists running five shifts a day, covering large swaths of the community. At the end of each shift the peers tally up the results—the number of people they contact, the number of needles they picked up, the number of times they call 911. Also on the list is the a column labelled “OD Responded,” meaning the number of times they aided somebody overdosing. Some nights, the Spikes on Bikes team deals with five to seven ODs. But the team takes pride in one aspect of that statistic: Vancouver’s highest overdose survival rate is in the Downtown Eastside, they say.

The program goes beyond the practical. Pandora says the bike itself offers something unique, sparking conversation and encouraging people to approach and open up, which isn’t always easy among a population in pain. “Some people are so out of it they don’t know how to respond to kindness,” Pandora says. “But the bike seems to help break through that.” Jonathan Orr, who helped get Spikes on Bikes started, says the image of the bike is just as important to the program as the practicalities of it. “The bike is a symbol of Vancouver,” he says. “It’s a symbol of innocence and openness, and it creates conversation. It’s made the team approachable.”

There are other lives wrapped up in this program as well: peers such as Pandora, who has dedicated so much of his life to helping people in his neighbourhood. Spikes on Bikes offers opportunities for addicts. While its purpose is to help people on the street, the program unexpectedly became a lifesaver for those working it, too. Pandora lists off a number of peers who have come through Spikes on Bikes from the street and into full-time housing and work. Pandora thinks the program gives peers purpose and dignity.

But it’s not easy. Orr says key to the program is an attitude of “radical acceptance.” That means employing people without judgement, which isn’t always smooth. Working with peers requires empathy and understanding ahead of rules. “Peers need time,” says Orr. “They need time to fuck up and fail and get angry and quit and be told they are welcome to come back.” Espousing acceptance can be easier than living it. There are nearly 40 peers involved in the program. When trying to schedule shifts and ensure paperwork is filled out, the idea of radical acceptance isn’t the most efficient way to get things done. But that’s not the point. “You know the stigma has been overcome as soon as they are invested in their own future,” Orr says.

Other challenges include a lack of money for the program, as well as resources. There are bigger institutional problems, too. “Decriminalization and getting people out of poverty so they can make safe choices, that’s the real solution,” Whidden says. “It’s criminalization of the poor. All of this is so preventable.”

But it’s the successes that drive everyone—not just by saving the lives of those overdosing, which can seem a daunting challenge in the midst of a crisis, but in the way the program is reaching into the community in more intangible ways. “People don’t see this, but this is a community,” Pandora says. “We’re part of it, and I’m proud of what we’ve done here.”

Which brings him back to that night he found his friend only moments from dying a lonely death between two Dumpsters. Pandora called 911 and began the process for reversing an opioid overdose. Naloxone works by binding to the opioid receptors in the brain, preventing the opioid from doing the same, thereby reversing the effects of the overdose. Pandora opened the naloxone kit, drew up the syringe and injected the formula into the man lying on the asphalt. Naloxone can work quickly. The man sat up with a start, and looked up to see it was his old friend who had just saved his life. “He had the biggest shit-eating grin on his face,” Pandora says, with a rueful laugh. “He was just so grateful.”

Tom Babin is a journalist and author who has written for The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times and Explore. He is the author of Frostbike: The Joy, Pain and Numbness of Winter Cycling. He lives in Calgary where he blogs about bikes at Shifter.info and rides his bike through all seasons.