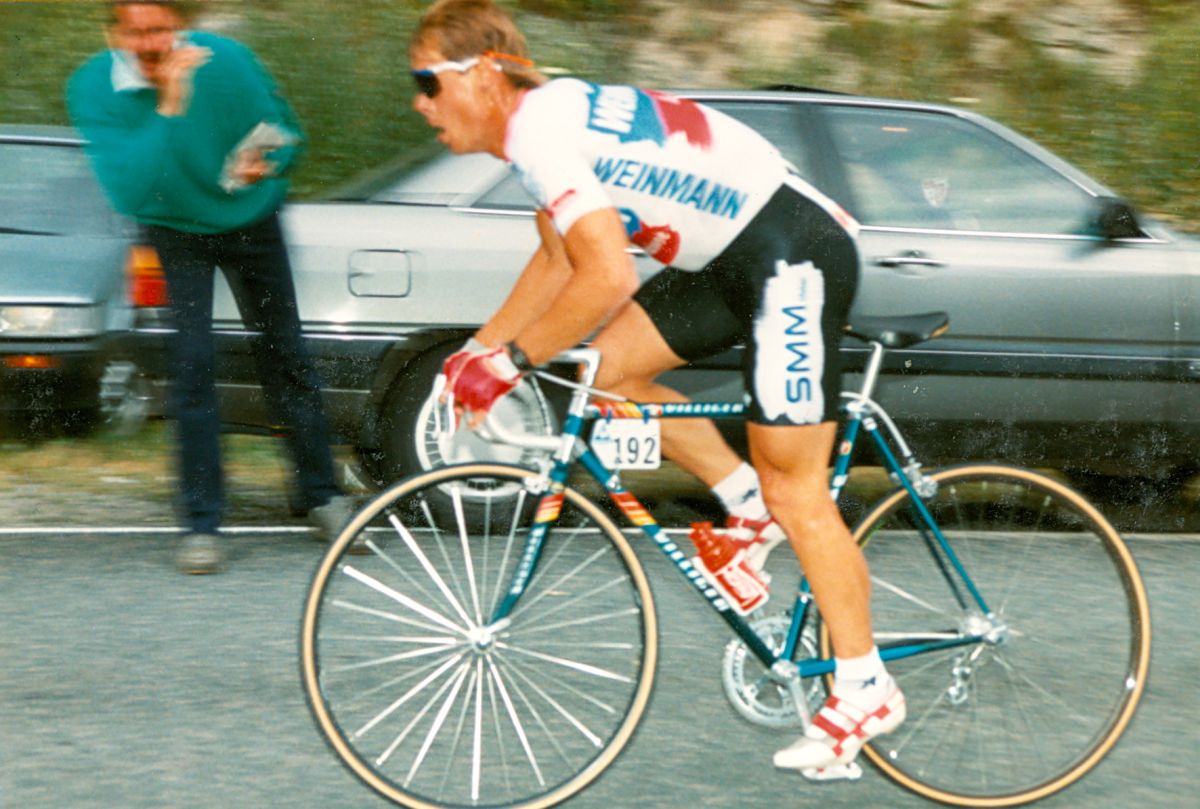

In a way, the first yellow jersey that Steve Bauer won at the 1988 Tour de France was set up two years prior. In 1986, fellow Canadian Alex Stieda broke away during the first part of a split stage. Because of the time bonuses Stieda had gained, he became the first North American to wear yellow. He had gone so hard on Stage 1a that on Stage 1b, a team time trial, both he and his 7-Eleven team struggled and he lost yellow. “Alex, he was proud he started that first stage in a skinsuit. He just went for it from the gun,” Bauer remembered with a laugh. Bauer himself was in that peloton riding for La Vie Claire with Greg LeMond and Bernard Hinault. In 1988, Bauer was on a new squad, Weinmann – La Suisse. “The stage was similar with a team time trial in the afternoon. No team would ever take full control of the early stage to save their energy for the team time trial. It gives an advantage to the breakaway, which Alex used. I was looking for a similar oppor- tunity in 1988.”Bauer and I spoke at the Grupetto Café in Dundas, Ont., surrounded by cycling memorabilia, some of it Bauer’s. It wasn’t too long ago, during one of Bauer’s seemingly rare stays in Southern Ontario. The St. Catharines, Ont., native spends months at a time in Europe working as director of VIP services for BMC Racing Team. The events we discussed, which had happened almost 30 years ago, he remembered surprisingly well.

“That stage was a bit broken,” he said of the morning race. “There was a union protest along the way, so the stage got stopped. The weather was crap. Nobody was really committed to the race. It was bizarre: not many attacks. It was almost like the peloton was rolling toward the finish. I decided, at about 7 km from the finish, to attack and open up the race. I got a bit of a draft from the vehicles in front – motorcycles and official cars. It gave me a good gap on the field. The peloton didn’t really commit until it was too late. I managed to hold of the peloton and win that stage and get the yellow jersey. It was a bit of luck, a bit of initiative and some solid fitness that carried me to that first Tour de France stage win.”

Before the French Grand Tour, Bauer’s year had gone well. In April, he was eighth at Paris-Roubaix. In early June, he won a mountain stage in the Tour de Suisse. “It finished on a descent,” Bauer was quick to add. He was second overall in that 10-day event. Next was the perennial TdF tune-up race, the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré. Bauer won the 93.2-km Stage 1b. Before heading to la Grande Boucle, the 29-year-old Bauer was likely in the best condition of his career.

He was on a new team in ’88, Weinmann – La Suisse. It, however, had familiar riders and staff. Paul Köchli, who had worked with Bauer on La Vie Claire, started the squad. The group that went to the Tour included Niki Rüttimann, a strong Suisse climber, who was also from Bauer’s previous team. Jean-Claude Leclercq was good in the mountains, too. Michael Wilson from Australia brought his skills as a solid domestique and time triallist. “We had a really good balance of talented individuals, maybe not one standout that people could say was a Tour de France winner. But collectively, we proved we were a really solid group of professional bike racers who could challenge the race,” Bauer said.

Favourites who lined up at the Tour that year included two-time winner Laurent Fignon and U.S. rider Andy Hampsten, who had won the Giro d’Italia less than a month before. Third-place TdF finisher Jean-François Bernard carried French hopes with him. Pedro Delgado had ridden against Stephen Roche in ’87 and lost out to Roche by 40 seconds. The first Irish rider to win the Tour didn’t return in 1988 because of chronic knee problems, but Delgado was back. Bauer’s former teammate Greg LeMond missed the Tour in ’88 as he still wasn’t in top shape following his hunting accident the year before.

“Going into the race, I wasn’t really thinking about who I’d have to beat to do well,” Bauer said. “I think I was more focused on the team and how we could ride to the best of our abilities.” Bauer felt that that outlook allowed him to achieve one of the best performances of his career.

After Bauer won yellow, Weinmann – La Suisse had to ride the team time trial later that day. He figures the presence of the jersey inspired the squad to ride harder than they might have otherwise. They couldn’t beat the powerhouse Panasonic team, whose ride put Teun van Vliet at the lead of the general classification. Still, Weinmann – La Suisse was second, 24 seconds behind Panasonic. While Bauer had fallen to ninth overall, the team’s work had set the foundation for the Canadian’s return to yellow.

Bauer had to be shrewd during that first week of the Tour. “When you are close to the lead, the key is looking for opportunities,” Bauer said. “You can’t really force it, unless you strong-arm the race on a stage that is particularly suited to you. For example, now in the Tour, it would be a mountaintop stage for a climber. It seems obvious there. But in the first week of the Tour, it’s not obvious. There’s rolling terrain with different types of finishes. You cannot lose time. And you look for those spots, like maybe a breakaway, that could get you that jersey back.”

On Stage 6, a 52-km individual time trial, Bauer put in an impressive ride, which got him within one second of the new leader, Jelle Nijdam of Superconfex. The next day, Bauer slipped a bit in the GC to nine seconds back. Of Stage 8, he remembered a short climb before the finishing city of Nancy, then a descent ahead of the final sprint. About 10 km from the finish, Bauer attacked. He pushed the pace. Nijdam got dropped from the main group. In the sprint, Rolf Gölz took the stage, but it was Bauer who pulled on the yellow jersey once again.

Next, Weinmann – La Suisse had to defend its lead. Bauer had more work to do both on and off the bike. “When you’re leading the Tour de France, there are other demands: anti-doping, media, attention from the to expend than if you weren’t in the jersey. I think the added pressure did not necessarily affect my performance.” Although the maillot jaune can bring extra work for a rider, it can also boost his abilities. The psychological term for this phenomenon is the audience effect. With people watching, with the responsibility to lead the team and defend the jersey, an athlete digs deeper and performs better than ever before. The yellow jersey gave Bauer a boost, a boost that far surpassed the extra duties that affected the race leader.

After Nancy, the stages started to feature more and more climbing, which wasn’t Bauer’s strength. Stage 11 from Besançon to Morzine included Pas de Morgins, Col du Corbier and high temperatures. “I love the heat,” said the rider from the great white north. “Everybody else was cracking.” Fignon finished 19 minutes off of the stage winner Fabio Parra. The French rider’s Tour was ruined. Bernard had a bad day, too. Both Sean Kelly and Robert Millar lost a lot of time. Bauer rode well and finished with the favourites, 23 seconds behind Parra.

The Canadian started the next day, which would finish on Alpe d’Huez, in yellow. He would face the Col de la Madeleine and Col du Glandon before the iconic climb. For Bauer, the final kilometres before the summit of Glandon were the toughest, tougher than even d’Huez. A large group of top riders where ahead, including Hampsten and his teammate Raúl Alcalá. Colombians Fabio Parra and Luis “Lucho” Herrera, and Charly Mottet and Peter Winnen. Farther ahead, Steven Rooks and Pedro Delgado were driving for Alpe d’Huez. After passing the summit of Glandon, Bauer blasted down toward the group at speeds he doesn’t think he’s matched since. “When you have the yellow jersey, you have to do what you have to do,” he said. Riding solo, he caught up with the Hampsten group.

Once they hit Alpe d’Huez, the initial steep inclines affected Bauer. He fell off from much of the group. He then rode his own pace. His team director, Köchli, kept giving him the times. Bauer knew he was still close to the jersey. He passed a shattered Hampsten and kept riding. Rooks took the stage, while Delgado rode into the lead. Bauer finished seventh, 2:34 behind Rooks and 25 seconds off of the yellow jersey. “It’s probably the best mountain stage I did in my career. I think the jersey helped as well as being in top shape,” he said.

After d’Huez, Bauer focused on a podium spot. He was third overall after Stages 13 and 14. He then kept fourth all the way to Paris. He had yellow for five stages and a stage win, the first for a Canadian. In 1990, he’d get the yellow jersey for nine stages. His fourth place finish in ’88, however, still stands as the best result for a Canadian at le Grande Boucle.

So many cycling performances from that time, unfortunately, come with asterisks. Questions about Delgados’ performance were raised before he had even finished the 1988 Tour. Probenecid, a drug that can be used to flush the residue of steroids from the kidneys, was found in Delgados’ urine. At the time, the drug was banned by the IOC, but it was still about a month away from being on the UCI’s list. Lucky for Delgado, it was the UCI’s list that took precedence. He raced on to win the ’88 Tour. In late 1999, the runner-up in 1988, Rooks, admitted in a television documentary that he had taken testosterone and amphetamines throughout his career. Bauer doesn’t seem to dwell on these injustices. He seems to bear them with the same stoicism that got him through the nine Tours de France he completed throughout his career.

When I asked him about the effect of his fourth place in ’88, he joked a bit about how there was no social media to bring the news to Canada quickly. But, he added that the media coverage at the time did inspire people to take up cycling or follow the sport. He’d heard that first-hand from many riders throughout the years. I think the effect grew as Bauer continued to race beyond ’88. In 2015, at the induction ceremony for the Canadian Cycling Hall of Fame, Lori-Ann Muenzer, Alison Sydor and Curt Harnett all cited Bauer as an influence. Riders too young to have seen Bauer race in the ’80s, such as Astana’s Hugo Houle and Milton, Ont., track rider Michael Foley, have benefited from Bauer’s experience and cycling wisdom gained abroad. Even the cycling-themed Grupetto Café in which Bauer and I spoke, about 80 km away from where the cyclist grew up, likely owes part of its existence to Bauer’s accomplishments. The influence of Bauer’s 1988 Tour on those younger athletes and the café may not be direct, but they do take from the glow of five days in yellow that happened 30 years ago.