The Moneyball of Canadian Cycling

How Kevin Field took data, and combined it with a lot of heart, to give this country some of its most significant successes of the past 15 years

In 2012, Michael Woods – Vuelta a España stage winner and world championship bronze medallist – was a broken runner with a new dream. The Ottawa native connected with Kevin Field and asked how he could become a professional cyclist. Field was a wellknown directeur sportif who had worked with the biggest Canadian trade teams of the past 13 years. “He gave me a challenge in that first meeting,” Woods says. “Score 100 UCI points.” Today, Woods says the goal was a perfect example of Field’s analytical methods. Forget chasing breakaways or KOM jerseys. Focus instead on scoring valuable points.

“He is the Moneyball of cycling,” says Woods, connecting Field with the book by Michael Lewis, subtitled The Art of Winning an Unfair Game. “He does a ton of data analytics and, like in many areas in life, the numbers rarely lie.” Woods broke 100 UCI points in 2015 and signed with Jonathan Vaughter’s Cannondale-Drapac Pro Cycling Team for the 2016 season.

“From my first races in the Gatineau hills, to competing against Valverde in the final metres of the world cham- pionships, Kevin has been working away in the background,” Woods says. Many of the top Canadian cyclists who have ridden during the past 20 years will tell you the same story: Field was key to building their careers.

The Moneyball analogy is quite appropriate for Field. He is to top-level road cycling in Canada what Billy Beane was to the Oakland Athletics in the early 2000s: an ana- lytical and brilliant mind who is able to get the most out of his athletes. Also like Beane, who was played by Brad Pitt in the 2011 sports film adaptation of the book, Field isn’t in it for the glory. He certainly isn’t in it for the money.

“Anyone who contributes to cycling has to get in and do it instead of just speaking about it,” says Steve Bauer, Field’s former boss at the SpiderTech-C10 team. “Kevin’s a doer. He’s a guy who will roll up his sleeves and do some contact work and get people excited about projects. His focus has always been on getting Canadians where they need to be, not for selfish reasons, but just making sure we believe in our guys and making sure they have a shot.”

In September 2018, where Canadians needed to be was Innsbruck, Austria for the UCI road world championships. In Field’s role as head of performance strategy for Cycling Canada, the sport’s governing body in this country, he was one of the architects of Canada’s team at the 91st worlds. If any single program is an example of Canada’s potential as a cycling nation, and Field’s abilities to motivate and bring riders together, this is it. After seven days of competition, Canada finished fourth overall.

“The worlds were huge,” says Matthew Jeffries, executive director of Cycling Canada. “To finish ahead of countries like Great Britain, who are putting millions into road cycling, and to do it on basically zero budget, was massive. We did it through collaboration and partnerships – and Kevin’s belief and ability to pull it all together.”

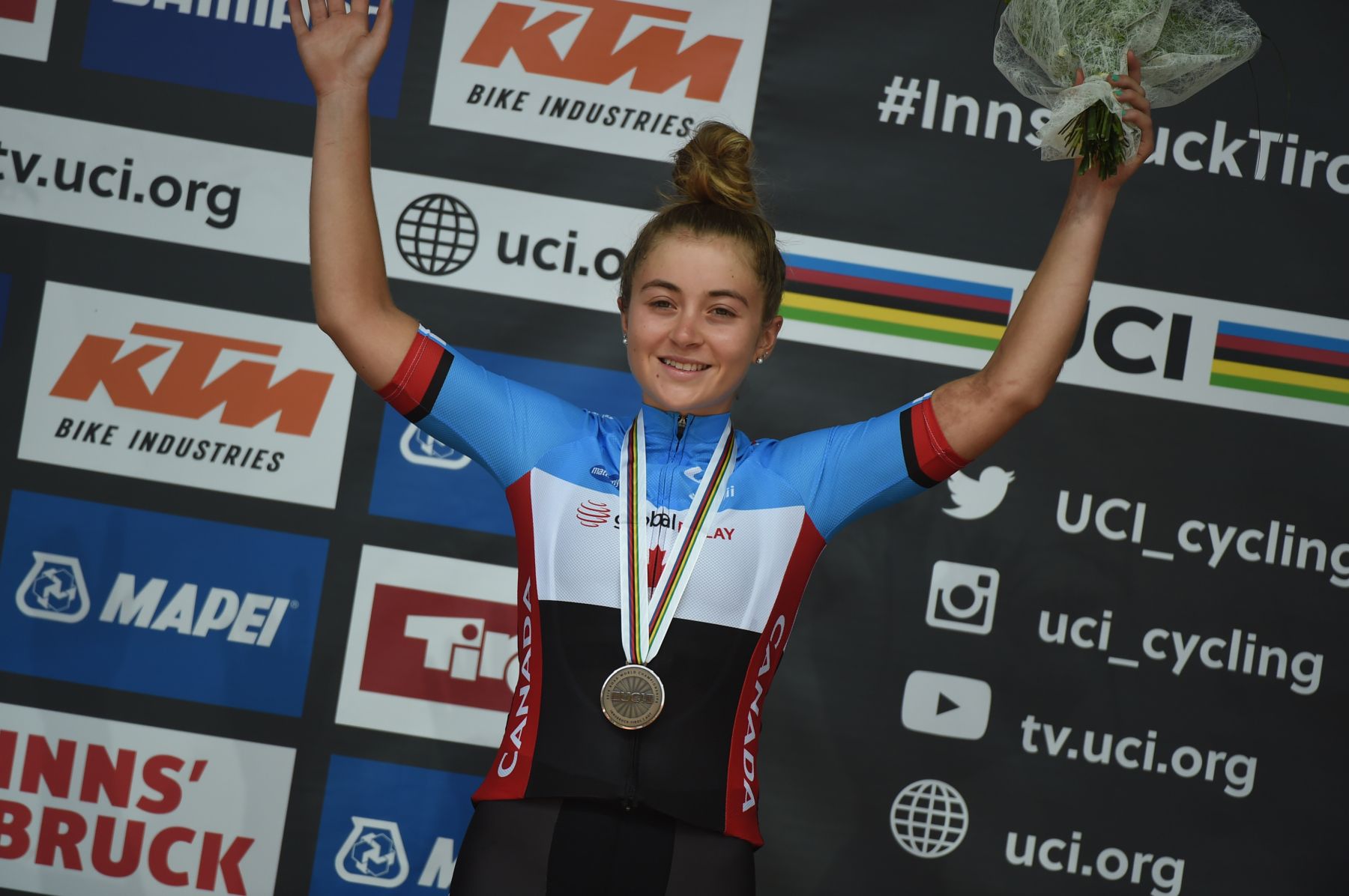

One of the biggest performances in Austria was by Simone Boilard. The rider from Quebec City rode to a bronze medal in the junior women’s road race. Of course, Woods finished third in the elite men’s road race, just behind world champion Alejandro Valverde and France’s Romain Bardet. A Canadian hasn’t done that since Bauer achieved the same result at the 1984 worlds in Spain.

There may have been no one who believed in Woods more than Field. He knew it was going to be a special day. It wasn’t just his gut that told him that. As Beane did with the Oakland A’s 20 years ago, Field trusted data. And the numbers didn’t lie.

Both within cycling and away from it, Field has bet his career on technology and data. As a web and digital specialist, he has launched five tech businesses, including The Feed, which he co-founded with Slipstream Sports president Matt Johnson in 2013. The analytical approach that made him successful in tech throughout the years is also what made him better at the organizational side of cycling than as an athlete. “As a rider I wasn’t terrible, but I wasn’t awesome,” Field says. He raced in the 1990s, but his focus was primarily on his business career.

It was near the end of that decade that Field made a change in cycling. He joined the Jet Fuel Coffee team, the first-ever Canadian UCI trade team started by Dave Butler in 1999. For the first two years, Field competed on the road, but eventually turned his attention entirely to being a director. “I realized I couldn’t do both at the same time very well, so I flipped to mostly just doing the directing,” he says.

“I give Dave a lot of credit for starting that team,” Field says. “Jet Fuel needs to be recognized for raising the bar and being the catalyst that led to a lot of teams like SpiderTech, Symmetrics, H&R Block and others.”

Symmetrics Cycling Team, launched by businessmen brothers Kevin and Mark Cunningham in 2005, was a direct result of the Jet Fuel team. “I didn’t know Kevin at the time, but he saw what we were doing with Jet Fuel and said, ‘Fuck those guys. We can do better than them,’” says Field, laughing.

The Cunninghams registered Symmetrics as a UCI trade team and hired half of the podium finishers from the 2004 national championships for the inaugural roster. Guys such as Svein Tuft, Christian Meier, Cam Evans, Will Routley, Andrew Pinfold and others were suddenly part of the country’s second powerhouse trade team.

Jet Fuel changed directions to more of a regional team for 2006, so Symmetrics picked up 2002 national champion Andrew Randell, as well as Field as a director, from those left out of work. “When I came in, the guys were on the cusp of doing great things anyway, but they weren’t ticking very well in the big races,” says Field. “Kevin Cunningham was an awesome guy and he wanted to win everything, so that winning DNA was already in the team. They just needed it pulled together a little bit.”

The team broke through in 2006, with Tuft, Randell, Pinfold and Eric Wohlberg combining for seven wins, including Tuft’s national championship time trial title. In 2007, Symmetrics was utterly dominant. In the UCI America Tour, the team won the individual rider title with Tuft and the overall team title. It also won nine races overall including the elite and under-23 national road race titles.

“The team became pretty awesome, pretty quickly,” Field says.

With riders committed to return to the team for the 2008 season, which included the Summer Olympics in Beijing, all was looking good until the global financial crisis hit and greatly affected the Cunninghams’ businesses, leading to a moment that Field and the riders working for him will never forget.

“Kevin couldn’t afford to keep the team going and the team’s budget was cut by 70 per cent,” says Field, recalling a team meeting at Kevin Cunningham’s house in November 2007 when the riders were told of the team’s fate. “I think that was a really important moment. At first the riders were all in a rage, but we sat down with the guys and made a plan.”

Riders who were in the room that night said what happened next would never have happened had it not been for Field’s leadership. They agreed to take pay cuts and stick with the program for one more year. “Kevin Field made it clear we needed each other to find jobs,” says Zach Bell. “It was because of him, but not because we owed him something. He was just very pragmatic about the fact that our best shot for moving on was to keep performing as a team.”

“We were pissed, but Kevin probably saved the program,” Andrew Randell says. “He made us see that it was still a good option and would allow us to showcase ourselves.”

Symmetrics’ final season was one of its most successful, highlighted by Tuft winning a gold at the national championships and silver at worlds in the time trial. “Svein and I had worked together for three years and it was the culmination of everything that team stood for,” Field says. “He is the epitome of the leader of a bike team and we became really close over that time. If we hadn’t kept the team together, I don’t think Svein would have been able to do that ride in Italy. He may not have raced that season, or be racing now.”

After Symmetrics, Field’s cycling journey took him to Trek-Livestrong as assistant director in 2010. He then came back to Canada to work for Bauer’s SpiderTech team in 2011 and 2012, where he was reunited with Tuft, Bell, Randell, Routley and others.

Field was hired to run Optum Pro Cycling’s women’s program in 2014, and then a year later by Cycling Canada to replace Gord Fraser in a role overseeing the national road programs and to work as a liaison between the governing body and the country’s top road athletes. He was also added as a strategic advisor to the Global Relay Bridge the Gap Fund, which was designed to help develop young Canadian cycling talent.

At the national level, Field saw inefficiencies and areas to improve the road programs. “I realized that the strong team-orientation style didn’t exist with the national team,” he says. “The way it functioned didn’t work. We picked riders late and we went for people who were good at the time. There was a certain Hunger Games aspect to it.”

Field brought Bell in to work with the women’s team in 2016 and the focus became eliminating conflict and getting the riders to work together. “I saw the opportunities as being even greater on the women’s side than the men’s,” Field says.

For Bell, who took over from Field at the renamed Rally Cycling team in 2016, reconnecting with his former director at Cycling Canada was another opportunity to learn. “I am always learning from him and I would like to think we’re at a point now where we’re learning from each other,” he says. “That’s been the beauty of working with him in my post-cycling career. Whenever we collaborate, it’s just about getting it done. There is not a lot of negative talk. It’s just brainstorming and solution-driven work.”

By the fall of 2017, the changes being made in the Cycling Canada road programs were starting to have an effect. Field could see big things on the horizon for the women, men and even the juniors. “It’s not like I had a crystal ball, but I just knew a lot of stuff was starting to line up,” he says. His gut feeling was backed up by the numbers.

“If you talk to anybody about the work that I do, I’m really into data and analytics,” he says. “They can’t predict the future, but they can give you a lot of hints and clues. When I looked at Mike Woods at that time, I was really excited about where he was and how quickly he was adjusting to WorldTour racing.”

After that 2012 conversation with Field, Woods turned pro with Team Garneau-Québecor in 2013. His inaugural season with Cannondale in 2016 included a second at Milano-Torino and a fifth overall at the Tour Down Under, not to mention competing for Canada at the Summer Olympics in Rio. His first two Grand Tours came in 2017, racing to 38th in the Giro d’Italia and an impressive seventh in the Vuelta.

Back in Canada, Field was working closely with Cannondale (now EF Education First) manager Vaughters, along with Woods’ coach Paulo Saldanha and privatesector-based sponsor B2Ten to work together toward Sept. 30, 2018, when the elite men’s road race would be held in Innsbruck. Field called B2Ten’s support of Woods and the wider national program massively important to the success that was to come. “All the pieces of the puzzle were there,” he says.

In October 2017, months before Woods would win the stage at the 2018 Vuelta and almost a year before the world championships, Cycling Canada held a national team camp in Victoria in an effort to strengthen the team-first focus that had become the new mandate under Field’s leadership. “Many of the key athletes we knew would be going to the worlds were there and it was all about team building, hiking, mountain biking, having fun and just talking about how to work together more cohesively,” says Jeffries. “A lot of the success that happened in Innsbruck was born in Victoria.”

Field also produced a pamphlet for sponsors and supporters inviting them to Austria the following year to witness what was going to happen. “There are times in life when you know something historic will happen,” he wrote. “Next September in Innsbruck, Austria, will be one such moment.”

That unwavering belief and support of riders is part of Field’s fundamental ethos when it comes to the organizational side of the sport. His modus operandi is to “create gracious champions who inspire a nation.” It’s an important statement to Field and one that he wrote down for himself in the early days with Jet Fuel. “I’ve always felt that there had to be more. It wasn’t enough to just win races,” he says. To Field, guys such as Tuft embody that concept of gracious champions who inspire Canadians. “I didn’t want to win with dicks and I didn’t want winning to be the ultimate goal,” he says. “I want to win. But you need great character and great talent to win in inspiring ways.”

On that final day of September 2018, when Woods ripped the legs off the top professional riders in the world during the finale of the 265-km world championship race, he clearly embodied that vision, as well. Although Woods was initially disappointed with not being able to beat Valverde for the win, everyone involved in the Canadian program was ecstatic. Bauer was the first person Field hugged after Woods crossed the finish line, and the tears were impossible to stop.

“For every guy of my generation, Steve was the icon who inspired us to race,” Field says. “To grow up and then meet him, work with him, become friends with him and then share that moment in Austria with him was…overwhelming.”

In the typical chaos that follows the completion of a major race, the Canadian team ended up spread out in various areas near the finish line and pit area. But Field called them all. They gathered about 30 minutes after the race was done on a quiet Innsbruck street. One by one, Woods’ teammates Rob Britton, Antoine Duchesne and Hugo Houle arrived. They were joined by some of the women’s team riders and the juniors, and then Woods rolled in with his coach Saldanha.

“We were able to share a really quiet moment together as a team. No crowds, just us,” Field says. Those are the types of moments that drive Kevin Field. It’s not about the glory or the podium or the recognition. It’s about helping elevate Canadian athletes and their sport.

“With him, the purpose is to develop and give back to the sport,” Jeffries says. “It’s always a bigger purpose than the performance. If you go back and look at the way the athletes were communicating on social media around the worlds, there was a real sense of team and family.

“Happy athletes are fast athletes. Kevin creates that environment and that’s why it’s so successful.”