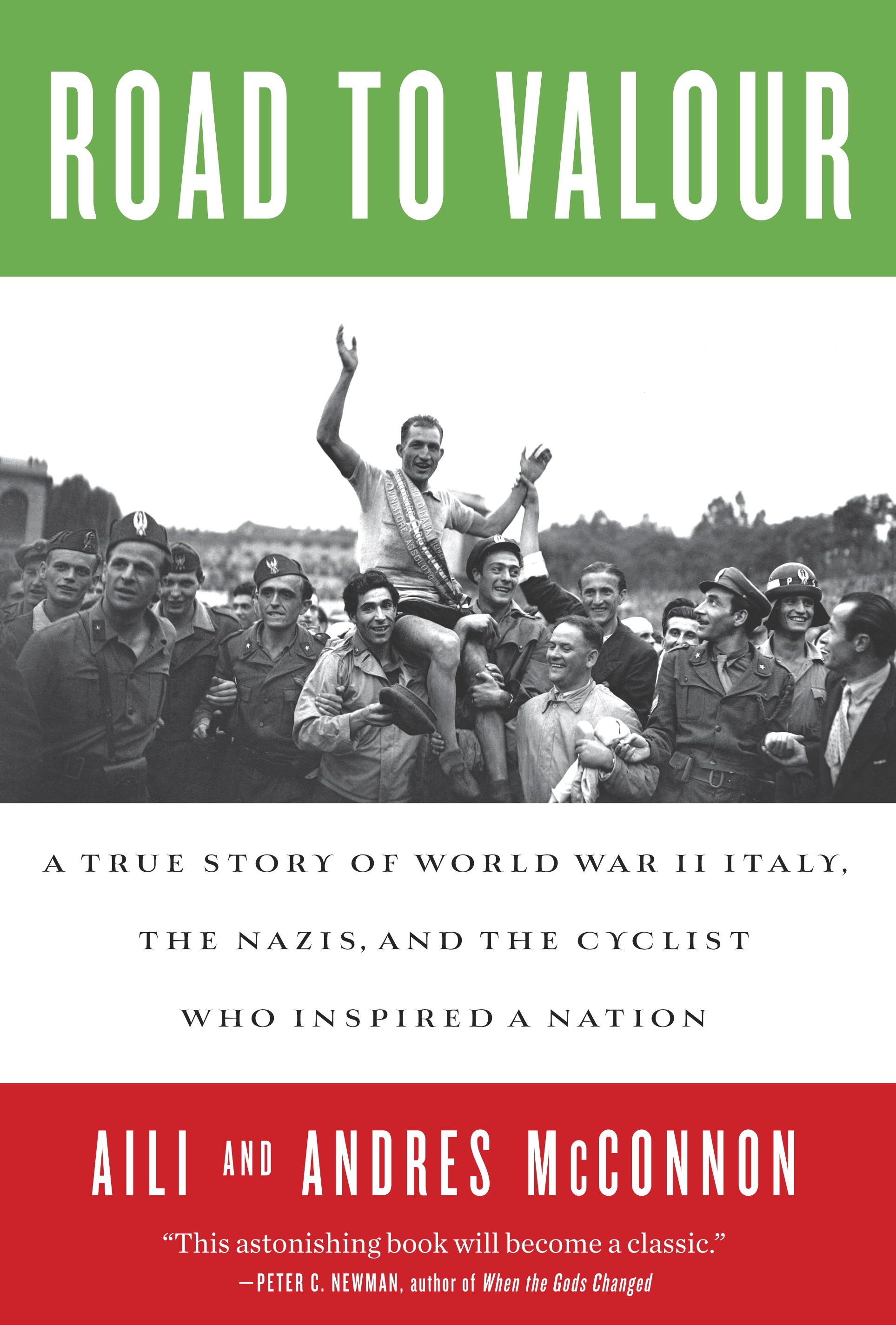

Book review: Road to Valour

Road to Valour (Doubleday Canada) offers bigger rewards to those not very familiar with Gino Bartali, the Italian cyclist whose career spanned the Second World War. Those who know of the racer’s victories and records will still get a lot from this book—from a look at cycling’s early history in the first half of the 20th century to European politics of the era—but they may miss out on the suspense. Some of Bartali’s races were infused with the same drama that comes with any good race. Others had much more than a coloured jersey riding on them.

Road to Valour (Doubleday Canada) offers bigger rewards to those not very familiar with Gino Bartali, the Italian cyclist whose career spanned the Second World War. Those who know of the racer’s victories and records will still get a lot from this book—from a look at cycling’s early history in the first half of the 20th century to European politics of the era—but they may miss out on the suspense. Some of Bartali’s races were infused with the same drama that comes with any good race. Others had much more than a coloured jersey riding on them.

Co-author Andres McConnon learned of Bartali through following the sport. He mentioned the Italian rider to his sister Aili, who was working on an anthology of literature on genocide and war. Later, she read about Bartali’s secret work during the Second World War to help Jews in Italy. The Canadian siblings then decided dig into the past and chronicle Bartali’s tale.

While their research is scholarly (the reference notes are impressive), the pair tell the story with all the drama of a work of fiction. All the background they found on Bartali, his family and others connected to the cyclist allowed them to recreate scenes in great detail, including dialogue. They start from his early childhood, move through his growth as a cyclist in pre-war Italy and onto his victory at the Tour de France in 1938. Although Bartali was a star in Italy, his Tour win wasn’t greeted with fanfare at home. In his acceptance speech, he didn’t thank Benito Mussolini, Italy’s Fascist dictator, which was a significant political gesture, as was the devout Catholic’s trip to mass the following day.

The second act of the book focuses on Bartali’s work to help Jews in Italy during the war. Bartali’s long training rides were cover for the cyclist to collect and deliver counterfeit documents that would help Jews to survive in Nazi-occupied Italy and, in some cases, escape. This story of Bartali’s humanitarian work hasn’t been well documented because he spoke little of it even after the war.

After the war, Bartali continued to be pulled into the political sphere. In fact, his ride in the 1948 Tour de France happened while his country seemed on the brink of civil war. Again, the cyclist’s actions played a role. It’s rare to see significant historical events linked so closely with cycling. When they are, it makes for a riveting read.