For author and sports physiologist Dr. Allen Lim, experience in the pro peloton taught that ‘you are who you eat with’

Lim is conducting seminars and book signings during the Toronto International Bicycle Show, and Canadian Cycling Magazine had a chance to chat before the weekend's festivities kicked off.

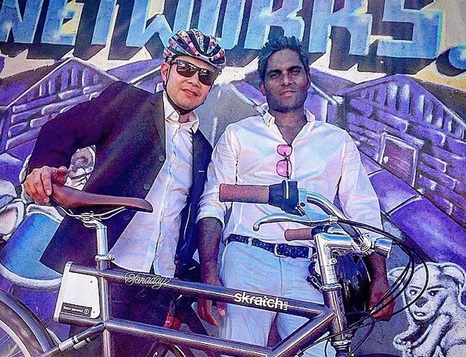

These gangsters, wrote a cookbook! Food is for the body as well as the soul! https://t.co/v6mhiTA3aW pic.twitter.com/ru11Fd23Ir

— Skratch Labs (@SkratchLabs) February 26, 2016

In Toronto this weekend, some of the biggest names in cycling—both gear and personalities alike—have descended on the Better Living Centre at Exhibition Place to mark the 2016 Toronto International Bicycle Show. Along with being the world’s largest consumer bike show, offering riders some great opportunities to snatch up everything from high-performance frames to groupsets, its also a chance to watch a bit of two-wheeling action and hear the thoughts of the pro peloton’s top experts.

One of those experts is Dr. Allen Lim, cycling coach, author, founder of Skratch Labs, and of course, a sports physiologist whose clients have included teams like TIAA-CREF, RadioShack and Garmin.

Lim is conducting seminars and book signings during the event, and Canadian Cycling Magazine had a chance to chat before the weekend’s festivities kicked off.

Notably, it’s his work as an author in recent years that has further Lim’s household name in the cycling world, having written cookbooks drawn from his experiences working with pro teams: Feed Zone Table: Family-Style Meals to Nourish Life and Sport, Feed Zone Portables: A Cookbook of On-the-Go Food for Athletes and The Feed Zone Cookbook: Fast and Flavorful Food for Athletes, all of which he co-wrote with chef Biju K. Thomas. The recipes offered defy the conventional wisdom that elevates prepackaged, high-energy products above regular food, with the latter described by Lim as better all-around for a rider’s performance. Instead of gels and energy bars, Lim prioritizes good, old-fashioned cooking and drinking for hydration as what a cyclist really needs.

But in terms of wellness, what he discovered as a sports physiologist goes a little further than just food, Lim said.

“I was hired to work with very young professional cyclists,” Lim said, looking back to the earliest days of his career working with young athletes in the pro peloton. “I think the expectation was initially that I was there to work on marginal gains, those little details that can make or break a performance. But when I got to Europe, what I realized was that marginal gains don’t really matter when there are all these bottlenecks.” The bottlenecks he described seemed to go deeper than what riders were eating. Many of the athletes were “lost,” he said, when it came to such basic things as cooking for themselves.

“The other thing that I found,” Lim added, “is that they were really lonely. Isolated and far away from home. Even though we were all on a team together, there’s that competition within the team that makes it sometimes difficult to really show vulnerability with one another. What I started doing was trade my sports science hat in for my home economics hat.”

That, Lim said, was when he found those major bottlenecks. Beyond the difficulty he encountered in teaching riders about optimal macronutrient combinations when they couldn’t even make a bowl of rice, he discovered a deficit of community on the team. Teaching them to cook—and, importantly, to cook together—offered a cohesive, intimate social dynamic that proved as healthy in the long run as the nutrients going into their bodies.

“The reality of being human is that we all need to belong,” Lim said. “When we saw down at the table and started bonding as a team, we started doing better, everyone just started doing better and that was really, really hard to quantify.”

For Lim, a big part of his approach to encouraging wellness for athletes stems from a philosophy that a cycling squad is another type of family—something he describes as “you are who you eat with”—and that like the flu or the comon cold, social contagion means that positivity or negativity can propagate just as freely among the members of a group. “When you think about certain diseases like cardiovascular disease, or even to think about something like happiness or loneliness, you don’t necessarily think of those as transmittable,” Lim said. “But in fact, if you become happy for some reason and you used to be sad, people within a one-mile radius of you have a 25 percent chance of being happier.” As social creatures, people—and especially athletes, competing in a tight-knit dynamic where sociability means as much out of the saddle as in it—tend to be sponges, Lim explained, assimilating the traits of their group.

“The idea here,” Lim said, “is that we have to be as aware of how not only we are doing, but those in our community are doing, because that ultimately affects us all.”

Going into his experience working with Garmin and RadioShack riders, among others, Lim quickly saw that the food his athletes made and the experience of eating it together went a long way towards fostering that healthy, close sense of community. It reflected his belief that the ritual of sitting together at the table to eat is one of the most important things that any social group can do, he said, simply for the sake of conversation and togetherness. In the cycling world, where “cycling widowhood” sometimes puts a strain on families, that principle can mean just as much at home as it does during training or on race day.

“I don’t think that the table will necessarily push your agenda,” Lim said, “[but] what it does do at least is it gets two people from different interests within the same family to sit down with one another and continue to be a family, continue to get to know one another to eliminate that cycling widowhood. It doesn’t mean that you need to have your spouse or your partner or your kids ride with you, but it does mean that let’s not have that sport or activity eliminate probably one of the most interactions of the day for a family, which is to sit down at the dinner table and just have a conversation.”

“I don’t care if we’re active together,” Lim explained. “I just care if we’re talking to one another, and maybe food can be the great facilitator for those conversations even if they don’t change someone’s interest level with respect to an activity.”

Looking back, Lim remembers the days when cyclists ate poor quality buffet-style food at hotels. Now, with nutrition having changed in World Tour ranks and teams at the Tour de France, for example, employing buses with on-board chefs, how does Lim think that other teams have borrowed the model he first developed working with Garmin?

“Outside looking in,” Lim said, “it’s hard for me to say how individual team cultures have changed. “Certainly I do know that people have adopted our portable recipes, rice cakes, eating real food after the stage as oppised to these liquid recovery drinks.” Other teams, he added, have rice cookers on their buses, a practice Lim developed—and with pride, advocated—with some controversy. The biggest difference is that pro teams are cooking whole foods for their athletes and nourishing themselves as a social group, Lim noticed, putting greater emphasis on the social dining experience itself—a practice he describes as embracing common sense.

“What I always knew was that the mood and the dynamic was always better if the food tasted good,” Lim said. “If the good didn’t taste good, then people would be sullen and the morale would be down. Maybe that’s an age-old proposition—that the morale of any team or organization is always built around the quality and the taste of the food—but I think now that people are emphasizing taste and emphasizing a higher quality of food, that that naturally improves the dynamic of the table.”

“We are extremely complex people,” Lim said, describing both pro athletes and fans alike, “but we have extraordinarily simple needs.”

Dr. Allen Lim will conduct book signings and seminars at the Toronto International Bicycle Show on Saturday, March 5 (11:00 am to noon at Booth #901, with seminars from 1:00-2:00 pm) and Sunday, March 6 (11:30 am – 12:30 pm).