The top 10 climbs in Canada for road cyclists

The best leg-straining, lung-busting routes in the country for you to ‘enjoy’

Climbing is the essence of cycling. Whether it’s the hill at the end of the driveway that defeats a little kid or a mountain pass where professionals battle for glory, climbs are what tie cyclists to the landscape. The rises in the land allow the riders to show their true ability. When describing a route, a cyclist always lingers over the climbs because they define the challenge—and the reward—that awaits. The truly great climbs are more than mere obstacles. They are expressions of the character of a place. They’re also the venues for epic competition. It’s no accident the names of the monumental climbs are synonymous with the biggest races in the world—the Poggio and Milan-San Remo, Alpe d’Huez and the Tour de France, the Stelvio and the Giro d’Italia. Canada may not have the cycling history of continental Europe, but there is no shortage of great climbs. Some are daunting physical challenges, others are famous only because they are popular cycling destinations or because they become—for one day a year—the venue for the world’s best racers. Compiling a top-10 list is an impossible task in a country this size—any list will omit more great climbs than it can include. (Yes, the climbs of Vancouver’s Triple Crown aren’t included, but we’ve focused exclusively on them here.) It would be easy to compile a list that’s in the B.C. Interior alone. So here’s an attempt to balance sheer physical challenge, cycling history and geographical distribution.

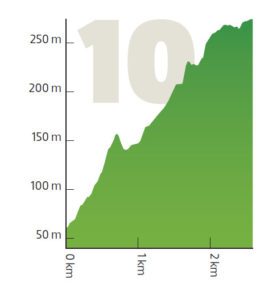

Cape Smokey, Cape Breton, N.S.

Cape Smokey, Cape Breton, N.S.

Length: 2.2 km

Altitude gain: 211 m

Average gradient: 9.4 per cent

Pro: Steep climb on a notable route; great views of the Atlantic

Con: Too short to be a true climbing experience

The Cabot Trail is a 300-km grind around Cape Breton Island, with plenty of climbing along the way. But of all the climbs, Cape Smokey best exemplifies the bleak majesty of the place. It’s not long, but it’s a leg-breaker, averaging more than 9 per cent when heading north. Cape Smokey was the scene of some epic racing in the early 1990s as part of the Tour of Cape Breton.

The Cape is still a popular challenge for cyclists. “It feels like it’s jutting out over the ocean much of the way. It starts out really steep, letting your legs know they’re in for some pain despite being at sea level,” says former national team mountain biker Jamie Lamb, who has done the entire Cabot Trail in a single day. “The view at the top allows most to justify a picture break as they catch their breath.”

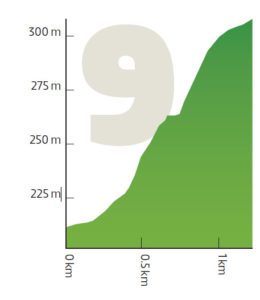

Rattlesnake Point, Milton, Ont.

Rattlesnake Point, Milton, Ont.

Length: 1.2 km

Altitude gain: 100 m

Average gradient: 8.5 per cent

Pro: Challenging climb that will have you using or wishing for a 27-tooth

Con: Rough road surface and popularity with motorbikes

It’s tough to choose a top climb in Ontario. It’s not that the province lacks hills: there are dozens of nasty climbs up the 725-km-long Ontario section of the Niagara Escarpment, which stretches from Niagara Falls to the tip of the Bruce Peninsula. Some have a strong racing pedigree: Beckett Drive in Hamilton hosted the 2003 road worlds; and Sydenham Road in Dundas was the scene of some tough Canada Cup road races in the 1990s. But the nastiest of them all is Rattlesnake Point in Milton, most recently used for the 2011 Canadian road championships.

The climb starts out as a gradual drag and gets steadily steeper as it twists to the top of the ridge, hitting 16 per cent before a hairpin under a thick canopy of trees that make the road slow to dry out after a shower: slipping rear tires are common.

“Rattlesnake is one I do fairly regularly as it is a rideable distance from my house,” says Silber Pro Cycling’s Ryan Roth, who lives in nearby Cambridge. “I also like to hit up the other Escarpment hills that are all close to each other, but Rattlesnake is definitely the steepest and hardest of them.” The challenge makes the climb a magnet for cyclists in the area.

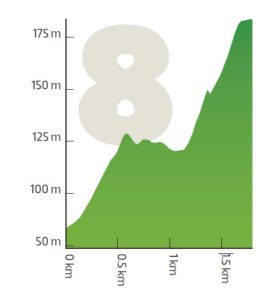

Voie Camillien Houde, Montreal

Voie Camillien Houde, Montreal

Length: 1.6 km

Altitude gain: 119 m

Average gradient: 7.3 per cent

Pro: Decades of cycling history in the heart of a major city

Con: Dodging Montreal traffic to get there

If any climb in Canada can claim status as a cycling monument, it’s the two-lane road that winds over Mount Royal. It’s here that Eddy Merckx won his third and final world road championship race in 1974. Also, it was the scene of the 1976 Olympic Games road race won by Swede Bernt Johansson. From 1988 to 1992, it was the venue for the Grand Prix des Amériques men’s professional race. Then from 1998 to 2009, it hosted a round of the women’s World Cup events. In 2010, men’s professional racing took over again with the Grand Prix Cycliste de Montréal.

It’s also one of the few places in Montreal where local cyclists can put in a solid effort without dealing with stop signs and traffic lights. “Mount Royal is a great place where I train several times a week all year long because it’s right in the middle of Montreal,” says Joëlle Numainville. “For me, the hardest part is the last 500 m. There’s often a strong headwind here. It’s a relatively fast climb. You have to give 100 per cent from the bottom to the top and make sure you accelerate on the flatter sections.”

Goldstream Heights, B.C.

Goldstream Heights, B.C.

Length: 7.7 km

Altitude gain: 340 m

Average gradient: 4.4 per cent

Pro: Good, hard climb to test yourself on

Con: Tough to get to without wearing yourself out

Victoria has just about the best year-round cycling weather in Canada, making it a base for many top riders. A popular training route for those riders takes in Goldstream Heights. It’s not for the faint of heart because it means a long day with plenty of climbing.

“From Victoria, you first have to climb the Malahat, which is a difficult highway climb. Then, normally, people do a lap around Shawnigan Lake or they ride around Mill Bay and Duncan,” says former national team rider Erinne Willock. “It’s a great climb that really starts at the bottom of Shawnigan Lake.”

The climb starts off on a rough road with some steep parts and some flat sections, before the freshly paved Goldstream Heights Road, which starts with a false flat and then gets progressively steeper toward the top, averaging more than 9 per cent for the last kilometre. The fastest riders take close to 20 minutes to do the climb and are rewarded with spectacular views of the ocean.

Highwood Pass, Highway 40, Alta.

Highwood Pass, Highway 40, Alta.

Length: 11 km (northbound) or 13.7 km (southbound)

Altitude gain: 326 m or 512 m

Average gradient: 2.9 per cent or 3.7 per cent

Pro: Highest paved road in Canada and great scenery

Con: Tame curves and wandering wildlife

Highwood Pass is not a particularly challenging climb. But at 2,206 m, it’s the highest paved road in Canada.

The pass is also a perfect illustration of how hard it can be to pin down statistics for many climbs. Depending on from where you measure, you could argue Highwood Pass is anywhere from 11 to 40 km long. But one thing is certain: the north side of the pass is tougher than the south side.

Given the high altitude, Highwood is only open to traffic from June to December. It becomes a cyclist’s paradise in May once most of the snow melts and the traffic-free route becomes rideable. It’s also used for the annual Highwood Pass Gran Fondo.

If the gradients aren’t too challenging, the altitude and the wind can conspire to make the climb very hard. Wildlife can be a hazard, too. “You have to watch for sheep on the road on the way down,” says Jeff Perron, president of the Rundle Mountain Cycling Club in nearby Canmore. Grizzly bears grazing in the roadside ditches are also extra motivation to keep moving.

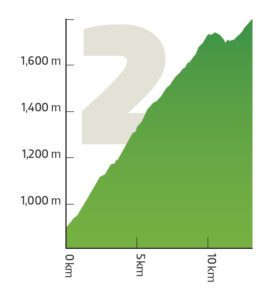

Mont-Mégantic, Que.

Mont-Mégantic, Que.

Length: 5.3 km

Altitude gain: 511 m

Average gradient: 9.6 per cent

Pro: Just about the only climber’s climb in eastern Canada

Con: Hard to get to and no amenities at the top

Eastern Canada isn’t known for its alpine terrain, but Mont-Mégantic is one place true climbers can stretch their legs. This lonely mountain 15 km north of the U.S. border features the highest paved road in Quebec, reaching an altitude of 1,106 m at the observatory on the summit. It’s also where the toughest stage in the Tour de Beauce ends, which always plays a key strategic role in the race.

In 2012, Quebec rider Hugo Houle showed he was an overall contender with a gritty ride to fourth place on the mountain on his way to second overall. In 2016, he was third on the Mont-Mégantic stage (Sepp Kuss of Rally was first) and second overall in the race once again. “The first 2 km of Mont-Mégantic are the hardest because they’re the steepest,” says Houle of Ag2r-La Mondiale. Because the gradient reaches 18 per cent, pros often use a 25- or even 27-tooth cog. “The front group always forms in the first kilometre—it’s very selective.”

There’s a brief respite where the road flattens out, but then it kicks up with 1,500 m to go. After a hairpin, it’s steep again as the road follows the contour of the mountain. The wind in the final, exposed kilometre can play a role as the riders’ legs get heavier. “That’s where the race is won,” says Houle. “The last 300 m are interminable and your legs are burning from the lactic acid.”

Tunkwa Lake, B.C.

Tunkwa Lake, B.C.

Length: 21.4 km

Altitude gain: 1,172 m

Average gradient: 3.6 per cent

Pro: Escape from the heat on a quiet road

Con: Nowhere to fill up your bottles

There are a lot of big climbs to choose from in the B.C. Interior, but it’s handy to get a personal recommendation from someone who’s good at finding the best ones. Few people have more experience than seasoned road pro and bike adventurer Svein Tuft. One of his favourites is the climb to Tunkwa Lake from Savona. He takes Tunkwa Lake Road, which runs south off the Trans-Canada Highway about 46 km west of Kamloops.

“It’s a super quiet road and you pass through a few different climates as you climb,” says Tuft. “In the heat of the dry Interior summer, it’s nice to get up in the high country and feel the cool air.”

It’s not a steady climb: there are pitches at more than 10 per cent and a few brief downhill sections along the way. But you can expect more than an hour of effort to reach the top. From there, it’s about 17 km to the mining town of Logan Lake and a nice, cold drink.

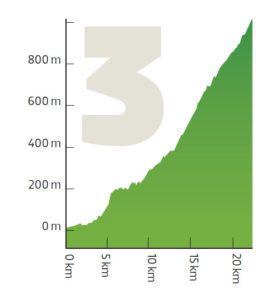

White Pass, Skagway, Alaska to the Canadian Border

White Pass, Skagway, Alaska to the Canadian Border

Length: 20 km

Altitude gain: 962 m

Average gradient: 4.7 per cent

Pro: Historic route that climbs to the Canadian border

Con: Only the last part is in Canada

If it hadn’t been for gold, White Pass might have been in Canada. In the 1890s, neither the U.S. nor Canada could be bothered to sort out exactly where one country ended and the other began in the frozen north. That changed in 1896 with the discovery of gold in the Yukon, triggering the Klondike Gold Rush. Canada kept the gold fields, but the U.S. controlled access through the port of Skagway.

Within a few short years a Chilkoot Indian trail became a major route for prospectors, first on foot and later by train. Today, the trail has become the paved Klondike Highway, peaking at White Pass 150 km from Whitehorse.

“The White Pass has spectacular views of the Skagway River Valley on one side the Pacific Ocean at your back, the rugged peaks of the Coastal Mountains in front and a sheer rock wall on the other side with numerous little waterfalls,” says Yukon cycling fixture Greig Bell, who is the father of former pro and current women’s team director at Rally Cycling Zach Bell. “You can pretty much see most of the way from the bottom to the top for the whole ride,” says Bell. “It also ends at the Canadian border which is kind of a cool goal.”

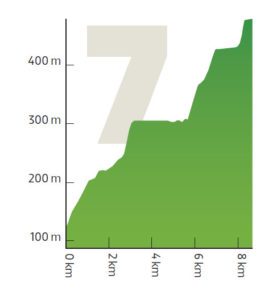

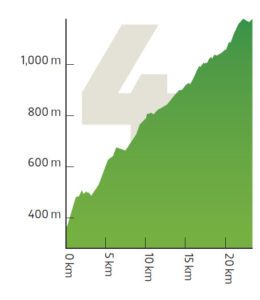

Apex Mountain Resort, B.C.

Apex Mountain Resort, B.C.

Length: 10.2 km

Altitude gain: 831 m

Average gradient: 8.1 per cent

Pro: Climb worthy of the Tour de France

Con: A lot of climbing to get to the climb

Hidden in the mountains just west of Penticton, B.C., is a climb that would rank among the toughest in the Tour de France. Making it even harder, the road from Penticton gains about 600 m in altitude over 23 km, making it a tough workout just to get to the turnoff onto Apex Mountain Road. Then the road kicks up to more than 10 per cent. The climb keeps going for another 10 km.

“As you get closer to the summit, it levels off a little bit. But the whole thing is quite steep, through

switchbacks, trees and the finish at a ski resort,” says professional rider Rob Britton, who races for

Rally Cycling. “It could easily be in the Tour.”

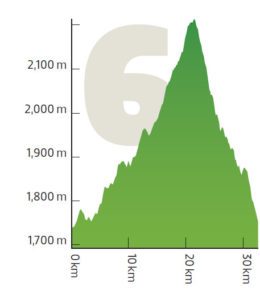

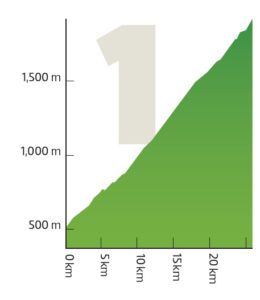

Mount Revelstoke, B.C.

Mount Revelstoke, B.C.

Length: 26 km

Altitude gain: 1,468 m

Average gradient: 5.6 per cent

Pro: The toughest climb in Canada

Con: The toughest climb in Canada

If you’re looking for an alpine climb, Mount Revelstoke is the place for you. With some 15 hairpins within 26 km, even the best climbers take more than an hour to slog their way up this monster. High in the Rockies, 415 km west of Calgary, the full length of the Meadows in the Sky Parkway is only open from July to September. Near the end of its season, the route is the scene of the annual Mount Revelstoke Steamer Hill Climb by the Revelstoke Cycling Association.

The climb starts right in the small town of Revelstoke, B.C., and is steady most of the way up. “The climb is not hard because of steepness, but because of the length of it,” says Brendan MacIntosh of Flowt Bikes and Skis. “There are a couple of tighter, steeper switchbacks. There is a short but more steep ‘wall’ with about 1.2 km to go.”

With the climb gaining nearly 1,500 m in altitude, there’s a distinct change of vegetation—from forest to no forest. Those who make the effort are rewarded with some fine views, a cabin at the top and some great hiking trails. Just make sure to have the proper layers for the long ride back down to the valley.