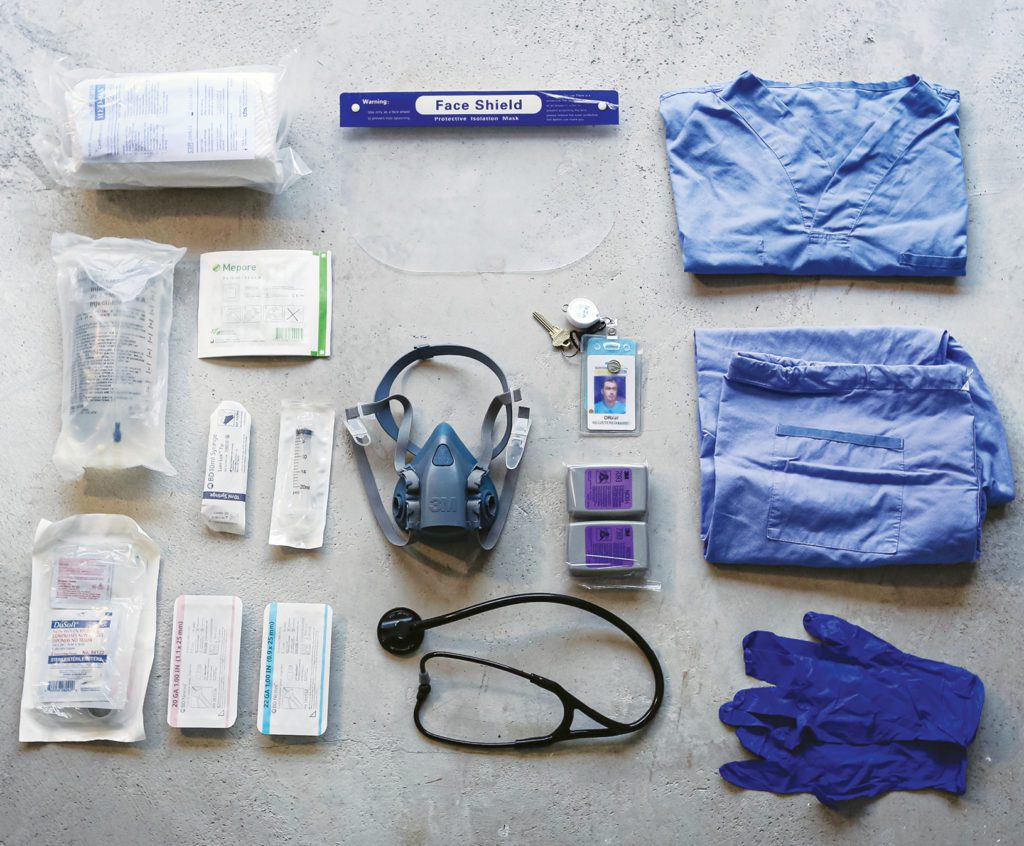

A registered nurse looks toward a return to his previous job: race photographer

Trading cameras and scrubs

Photo by:

Oran Kelly

Photo by:

Oran Kelly

By Oran Kelly

The cheers and applause echoed among the downtown high rises. It was a familiar sound that I have heard many times before, on the nearby streets of Gastown, the historic city walls of Quebec, elevated alpine passes or the pavé of northern Europe. But in the spring of 2020, the cheering sounded different. It was as passionate, but without joy. The time was 7 p.m. I was about to start my night shift in the emergency department of a Vancouver hospital.

When a pandemic was declared on March 11, 2020, I knew that my skills as a race photographer were of little useful contribution. It was my skills as an emergency nurse that would be called into service.

With the name Kelly, it wasn’t hard to find an Irish cycling King to follow in my childhood. Adjusting the TV set top bunny ears at my granny’s house during summer vacations was the obligatory start to watching the Tour coverage. I had a poster of Stephen Roche in the maillot jaune on my bedroom wall. After I completed university and gained employment as a registered nurse in the ER, I had a flexible shift pattern that coincided with many of the Classics and even stages of the Tour.

In 2008, I moved to Canada and continued working in emergency nursing. In North America, with fewer races close by and more expensive travel costs compared with Europe, I knew that I would need to maximize my roadside peloton glimpses. At the 2009 Tour of Missouri, I spent the night before each stage poring over the road book and examining estimated race speeds to find the maximum number of race-watching opportunities each day. The dirt back roads of Missouri that intersected the race route afforded prime viewing opportunities in eight to 10 spots per day. On the morning of the final stage, a Missouri state trooper on moto duty for the race said to me in a fine Midwest drawl, “Sir, every day I see you all over the course. I don’t know how. I don’t want to know how. But mighty impressive.” He tipped his hat and left. Later that day, the race photographer pulled up beside me and asked if I was Belgian, as he’d seen me at multiple points along the race. He noticed my camera and asked if I had any decent shots. After I showed him a few, he asked for my contact info. Later, he asked me if I’d be interested in helping to cover future races. With the inaugural US Pro Challenge in 2011, I began the transition away from full-time emergency nursing to race photography.

While the roles of race photographer and emergency nurse are distinct entities, there are facets from each that have intertwined over the years. A vital component of ER work is the rapid initial assessment. Triage is not dissimilar to looking at riders as they take the start, taking in early indications of who to look out for that day. Passing through the peloton on the moto, I look to see who is breathing easy on the early sections of the climb, who is sitting in, shoulders dropped and relaxed. These days I look for the opposite: respiratory patients in a tripod position as they search for more oxygen, struggling up their own hors category climb in their battle against the invisible gradient of COVID-19.

On a night shift in early September last year, a familiar, subtle odour of aviation fuel drifted into the trauma bay from the helipad through the HVAC. It was an early warning to prepare for what was about to begin. It’s a similar olfactory anticipation to the faint exhaust fumes from a BMW 1250 GS as they seep into the moto helmet at the start line. I was reminded that, if not for the pandemic, I would have been arriving in Quebec City at that time.

For more than a decade, the end of summer heralded the return of the Grands Prix Cyclistes de Québec et de Montréal, which are set to return in 2022. The UNESCO World Heritage site of Quebec City provides a scenic backdrop to the peloton as it races through the only remaining fortified walled city in North America north of Mexico. The circuit gives me a variety of opportunities to shoot the action on foot from different perspectives, which rarely happens with a point-to-point race. Montreal has a less fairy-tale touristic feel. Still, it’s a city that knows cycling. Eddy Merckx won his third world championship there in 1974 on a route similar to the Grand Prix’s, which takes advantage of the grades of Mont Royal. The course lacks the random tourists of Quebec City, replaced instead by a multitude of race fans, many on their road bikes, who crisscross the course to watch the action. The descent of Polytechnique and the tantalizing, almost hidden from view, final sprint perspective of the finish line are my favourite aspects of Montreal.

Back when the zenith of Canada’s third wave of COVID-19 receded, I began to anticipate my return to race photography. The end of this pandemic will mean so much to so many. To me, it will mean I can trade in cardiac monitors and O2 alarms for the crescendo of yelling and the enthusiastic ringing of cowbells by finish-line fans. I can kneel in the finish-line photographer area, the elite of the cycling world sprinting up Grande Allée, my only concern: controlling my own pulse and respiratory rate.

I look forward to reflecting on the privileged and fortunate positions I hold in all roles, but mostly I look forward to passionate fans enjoying the spectacle of bike racing, cheering with joy.

This story originally appeared in the August/September 2021 issue of Canadian Cycling Magazine.