Three books about cycling for your holiday reading list

Pick up a copy of We Begin Our Ascent, Riding into Battle or Muscle on Wheels to have something good to read when you have some time off

We Begin Our Ascent

written by Joe Mungo Reed

published by Simon and Schuster

reviewed by Matthew Pioro

What leads a cyclist to dope? Tyler Hamilton’s The Secret Race and Thomas Dekker’s The Descent are fairly successful works of nonfiction that tangle with that question. In English writer Joe Mungo Reed’s work of fiction, We Begin Our Ascent , doping creeps into the story. In a way, Reed’s book details how a pro cyclist turns to cheating with more subtlety and nuance than former riders like Hamilton and Dekker.

While pro cycling and the Tour de France feature prominently in the book, it’s about more than those topics. Sol is a successful domestique, but one whose ambitions have limits. His wife Liz is a driven geneticist and struggling to make a scientific breakthrough. They’re both high-achievers, yet also an average couple with a young son trying to make their lives work.

Reed’s portrayal of professional cycling is quite good. He captures the complicated dynamics of the team sport and the pain and suffering that happens out on the road. He does have some turns of phrase that are curious. In one sentence, he refers to a directeur sportif and a race referee. It seems odd that he would use “race referee” instead of “commissaire,” especially since he didn’t opt for “sporting director” or “coach.” These are just minor distractions from the otherwise well-constructed world.

So what leads Sol to dope? His amoral director, Rafael, does have a role in it, as does the rider’s own desire to contribute to the team. Liz, too, helps her husband make the decision. As with any good work of fiction, their decisions seem inevitable. You’ll likely find yourself sympathetic with their choices, regardless of how destructive they are.

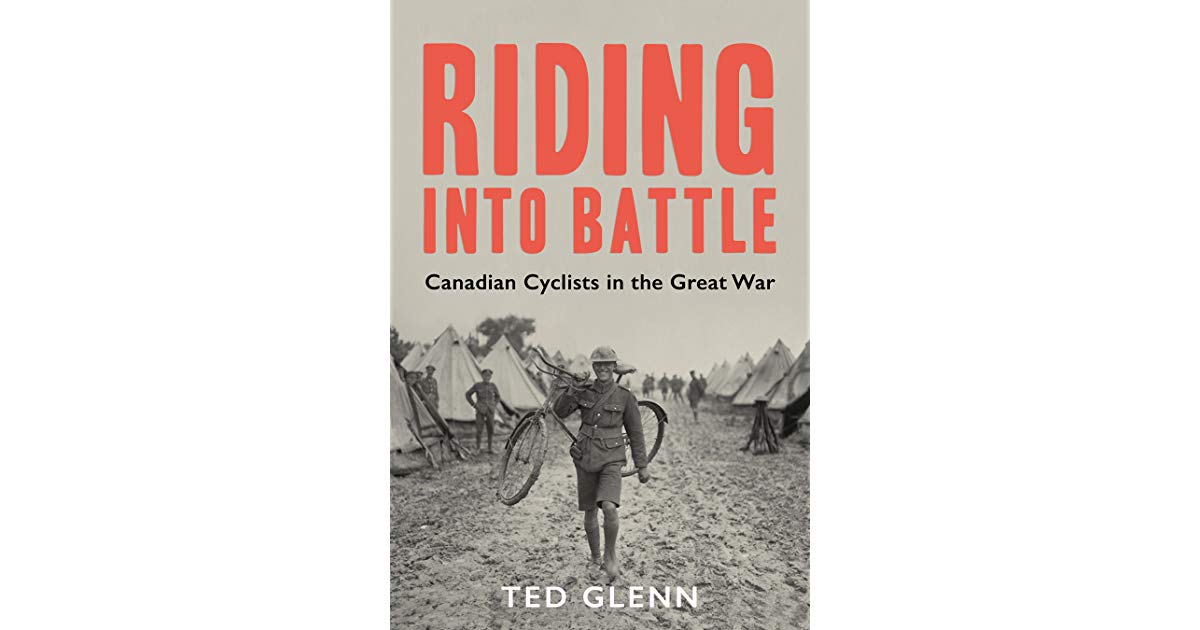

Riding into Battle

written by Ted Glenn

published by Dundurn Press

reviewed by David McPherson

Did you know that the Boer War saw the introduction of battlefield cyclists riding as light cavalry and performing duties such as reconnaissance, scouting and communications? After reading Ted Glenn’s Riding into Battle , I was struck by the role bicycles played in early modern warfare. I was also fascinated by the young men of the 1st Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion who came into their own – especially during the pivotal 100 Days Campaign toward the end of the First World War.

The story begins in three locales: Valcartier Camp north of Quebec City, Camp Exhibition in Toronto and Paradise Grove at Niagara-onthe-Lake where the five original divisional cyclist companies were organized and put through basic training between September 1914 and April 1916. The bikes were not sleek racing machines; rather, the full cyclist kit in the Great War weighed in at almost 90 lb.

Researched with rigor, and devoid of an academic’s style, the Humber College professor’s prose chugs along with a steady cadence. Glenn shares stories of two-wheeling Canadian war heroes. Interspersed are incredible period photos that help take the reader to the battlefronts. Overall, this book is a welcome record of Canadian military history. More important, Glenn succeeds in his goal to fill a gap in the history of Canada’s part in the Great War by illuminating the valuable contributions of Canadian cyclists in its outcome.

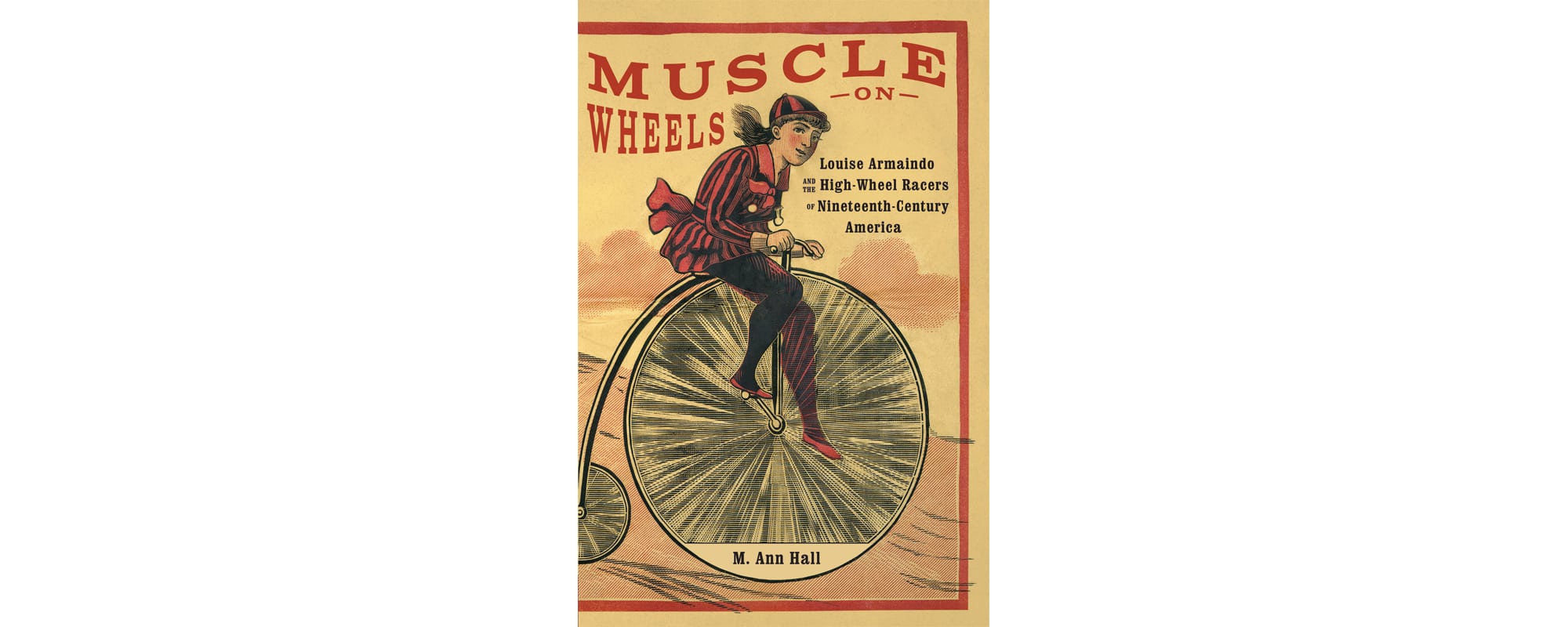

Muscle on Wheels

written by M. Ann Hall

published by McGill-Queen’s University Press

reviewed by Matthew Pioro

Retired professor M. Ann Hall’s Muscle on Wheels is not only a work of biography and history, but of mystery as well. Hall chronicles the life of Louise Armaindo, a French Canadian high-wheel racer who competed in events largely in the U.S. and Canada from about 1881 to 1893. The racer got her start in the circus as a strongwoman and trapeze artist. (Supposedly, her mother was a strongwoman, too.) “Armaindo” is a nom de circus , so finding the cyclist’s real name and place of birth was difficult and ultimately inconclusive for Hall. It didn’t help that circus performers of the day often embellished their biographies.

Armaindo moved from the circus to pedestrianism, essentially long-distance walking competitions. Next, it was the endurance challenges of high-wheel races as well as trick riding. There were a few other women racers; Armaindo competed mostly against men, and horses, too. These events could draw crowds of thousands.

The Canadian rider’s skills seemed to wane in the 1890s, which was also the time that the safely bicycle, which got its name partly because it was way less treacherous to ride than a high wheel, began to grow in popularity. Off the race course, Hall documents how the safety not only got more women riding, but provoked a quick backlash against those same women. The League of American Wheelmen didn’t seem too threatened when there were only a few women riding and competing on high wheels. In 1895, however, its rules stated that races wouldn’t receive sanction if they included women. Still, the racing continued. In Canada, the first women’s six-day safety race ran in Winnipeg, in June 1896.

Armaindo’s end is almost as mysterious as her origins. She was a patient at a hospital in Buffalo June 1, 1890. Then, somehow she got to Montreal where she died on Oct. 12. Records show she was buried in the cemetery associated with Notre-Dame Basilica. Yet, Hall has not been able to locate Armaindo’s grave.