The Amazing Race’s Phil Keoghan on retracing the 1928 Tour de France

Television host created the documentary Le Ride to tell story of New Zealand's first rider in the Tour, Harry Watson

“Ben and I were hallucinating going up the Tourmalet,” said Phil Keoghan, host of The Amazing Race. He was speaking about the ride he and his friend Ben Cornell did in summer 2013, retracing the route of the 1928 Tour de France for a film called Le Ride. That Tour, at 5,371 km (3,338 miles) was one of the longest Tours ever. Stages averaged 240 km, seven were longer than 322 km. The riders climbed 40,234 m in 26 days. Stage 9’s winner in 1928, Victor Fontan, covered the 363 km from Bayonne to Luchon in 18.5 hours. It would take Keoghan and Cornell more than 23 hours to do that stage.

“The road was putting us into a trace. It was weird,” Keoghan said. “I was convinced that the 1928 peloton was ahead of us. Absolutely convinced. No doubt in my mind that they were just around the corner. I was going to see them. They were going to be ghost-like, but there on the road.”

“Ben and I were looking after one another. We were postal weaving up there because it was quite steep. It’s not like were were riding with compact gears,” he said. The pair were riding period-correct, or at least as-correct-as-possible, bikes. Keoghan was on a Ravat Wonder. He had five gears—two on one side of the rear axle, three on the other. To change gears required Keoghan to stop, loosen the wheel from the frame, place the chain on the new cog, and then tighten everything up. It took Keoghan two years to source that bike, which didn’t fit him. (“It actually had the worst riding position you could imagine,” he said.) It needed to be rebuilt. Off went the 165-mm long cranks. He had to have a special seatpost made, in the shape of a “7,” to get himself farther forward. Then he needed the stem extend. The wheels needed to be rebuilt, too. Keoghan put a modern saddle on because there was only so much pain he was willing to put up with.

The visions during the ride kept running through Keoghan’s mind.

“I realized I had seen giant sperm on the road, the size of Volkswagen Beetles, swimming up the road,” he said.

“The next morning at breakfast, I said, ‘Ben, did you see— I know this sounds crazy, but did you see the sperm on the road last night?’ He started laughing and said I was out of my mind.

“I said, ‘Ben, I’m telling you, I saw them!’

“He said, ‘Yeah, and you also thought the peloton was up there.’

“‘Well you saw things, too. It’s not like I was the only one.’

Months later, when Keoghan was back in France to shoot aerial photography for the film he, Cornell and others were working on during that ride, Keoghan realized that the sperm weren’t a hallucination. They are painted on the road near Voie Laurent Fignon. The 1928 peloton did remain an apparition that the pair never caught. In as sense, Keoghan’s documentary Le Ride is all about chasing that pack from 89 years ago. He was trying to capture one rider in particular.

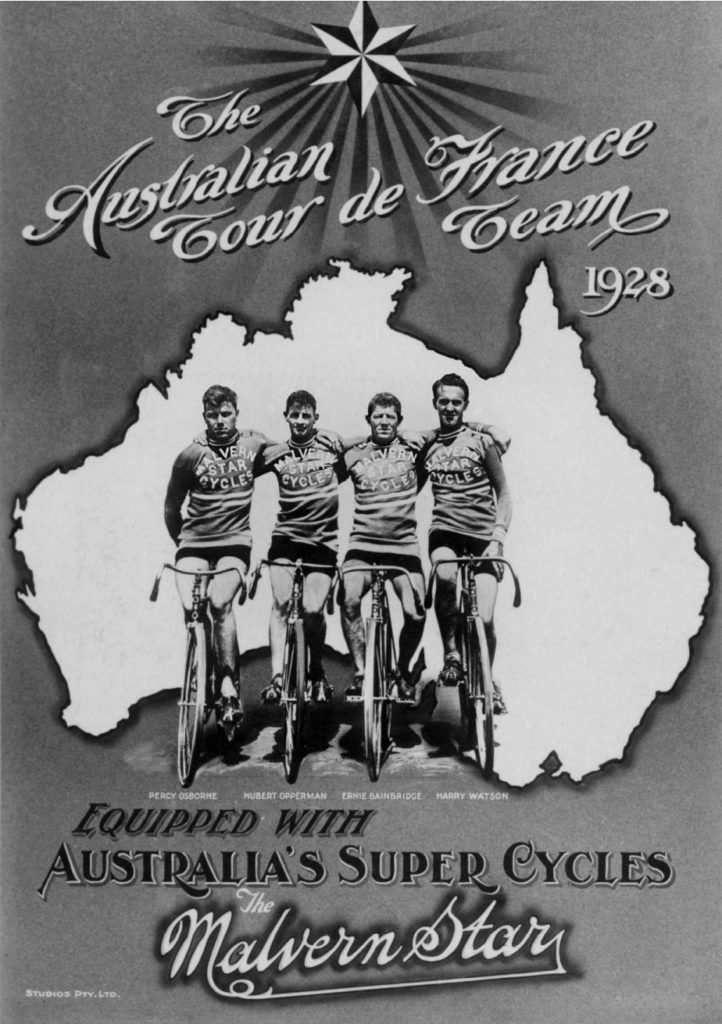

When Keoghan discovered Harry Watson: The Mile Eater, a book by Jonathan Kennett, Bronwen Wall and Ian Gray, Keoghan was shocked. It detailed the life of Watson, New Zealand’s first rider in the Tour de France. Keoghan, a passionate cyclist (from 2011 to 2013, he and his wife, Louise Keoghan, helped to run the women’s pro team Now and Novartis for MS) was surprised that he had never heard of Watson, even though the pioneering rider was from a place near Keoghan’s hometown of Lincoln, New Zealand. Watson was part of the Tour’s first English speaking team and a seven-time New Zealand champion. Keoghan asked pro cyclists from his home country about Watson and they’d never heard of him. Even Watson’s son didn’t know of his father’s accomplishments. “When I had met Harry’s son, who was then 86 and was born when Harry Watson was in the Tour de France, his son had welled up when I showed him newspaper articles of what his father had done in France, because he had known nothing about it. His son!” Keoghan said.

“Watson would go to Australia and take part in big races,” Keoghan said. “The only guy who could beat him was Opperman. And sometimes, Watson would beat Sir Hubert Opperman. They were one and two in Australasia. So, it made sense that when Sir Hubert Opperman put his Tour de France team together, that he’d ask Harry Watson.

“But Watson would do these races and not tell anybody. Nobody would get the news of how successful he was. In our culture, in New Zealand, it’s a little like the Canadian sensibility: you don’t show off. There’s almost an expectation in New Zealand that if you are a high achiever, you downplay your success. So, Watson would come home and not say anything.”

While Watson’s humility really spoke to the New Zealand psyche, Keoghan and his wife decided that they had to tell Watson’s story. They could let the rider’s modesty keep him in obscurity. But how to document a ride that happen so long ago, its main actors gone and its archival footage mostly black-and-white images? “We needed to get inside the story and bring it back to life,” he said. “That’s the idea for juxtaposing our ride in 2013 with the ride of 1928—stage by stage, ride the same miles, go over the same roads, go to the same town and experience what they went through so that we can bring the story of 1928 to life for an audience.”

Le Ride is screening for one night on Aug. 23 at Cineplex theatres across Canada.