UCI reveals results of technological fraud tests from 2023 Tour de France

International cycling body posted details on Tuesday

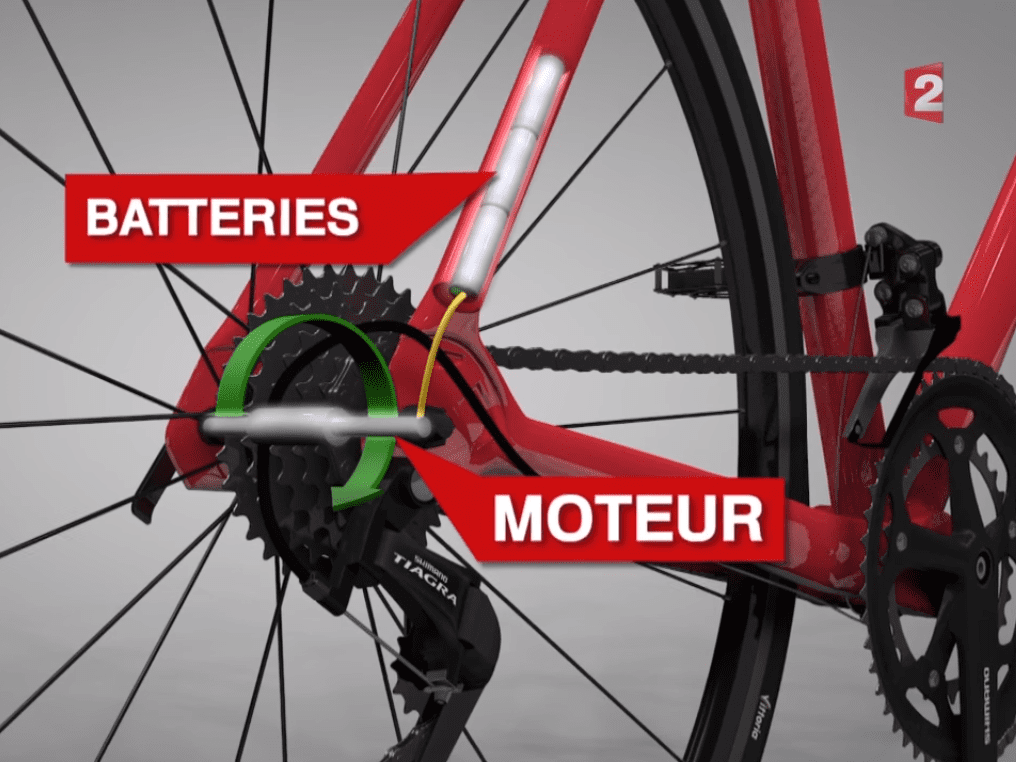

The Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) announced the details and results of the tests carried out at all 21 stages of the 2023 Tour de France as part of its programme to fight against technological fraud on Tuesday. According to the UCI, the tests look for the presence of any propulsion systems hidden in the tubes or other parts of the bike.

There were 997 tested conducted in total, and all came back negative.

Jonas Vingegaard claps back about doping after incredible climbing speeds

Out of all the tests performed, 837 were executed prior to the start of the stages, utilizing magnetic tablets. Additionally, 160 tests were conducted at the conclusion of the stages, employing either backscatter or transmission X-ray technologies.

Before the start of each stage, a UCI technical commissaire used magnetic tablets on all of the bikes in the team stalls.

Subsequent to each stage, tests were conducted on the bicycles utilized by the stage winner, the rider wearing the yellow jersey, and six other cyclists who were chosen randomly or those who might arouse suspicion.

Jonas Vingegaard to visit home for elderly as part of Tour de France celebrations

“The large number of tests carried out at the 2023 Tour de France as part of our technological fraud detection programme sends a very clear message to riders and the public: it is impossible to use a propulsion system hidden in a bike without being exposed,” UCI director general Amina Lanaya said. “To ensure the fairness of cycling competitions and protect the integrity of the sport and its athletes, we will continue to implement our detection programme and to develop it further”.

The history of motor doping

Over there years, rumours of motor doping has been rampant–but only one athlete has actually been caught with using it. One of the initial instances of suspected mechanical doping dates back to the 2010 Tour of Flanders, where Fabian Cancellara’s unconventional seated attack on the steep Kapelmuur sparked accusations of an electric motor concealed in his bike.

The controversy resurfaced four years later in the 2014 Vuelta a España when Ryder Hesjedal faced allegations of mechanical doping. Following a crash on stage seven, video footage captured his bicycle’s rear wheel persistently spinning even after it had toppled onto the road.

Testing for motors

Under public scrutiny, the UCI succumbed to pressure, prompting race commissaires to scrutinize the bicycles of Hesjedal’s Garmin–Sharp team the next day. Despite the thorough examination, no motors were discovered. Subsequently, in the ensuing spring, inspections for bike motors were conducted at prestigious events such as Paris–Nice, Milan–San Remo, and the Giro d’Italia. Bikes are now tested regularly, using an iPad.

There have been suggestions over the years that Lance Armstrong had a motor in his bike. He would often tug at the back of his shorts during a race, and some wondered if he was somehow hitting a button. When asked, he emphatically denied (motor) doping. “In 1999 no one even knew you could put a motor in a bike,” he said in a Cycling Weekly article.

To date, the only cyclist to ever be caught is Belgian Femke Van den Driessche. During the 2016 ‘cross worlds, the UCI discovered that one of her spare bikes had a motor in it. She denied that she intended to cheat, rather that it was a friend’s bike that had been put there by accident.