A deep dive into the history of motor doping in cycling

The issue of technological cheating continues to dominate discussions in the sport

Over the years, rumours of motorized cheating in cycling have abounded. One of the first suspected cases of mechanical doping dates back to the 2010 Tour of Flanders. That was where Fabian Cancellara’s unorthodox seated attack on the steep Kapelmuur led to accusations of an electric motor hidden in his bike.

The controversy resurfaced in the 2014 Vuelta a España. Ryder Hesjedal faced allegations of mechanical doping after a crash on Stage 7. Video footage showed his bicycle’s rear wheel persistently spinning even after it had fallen to the ground.

Afterward, the Canadian vehemently denied the accusation, saying it was simply not possible.

The origins of testing

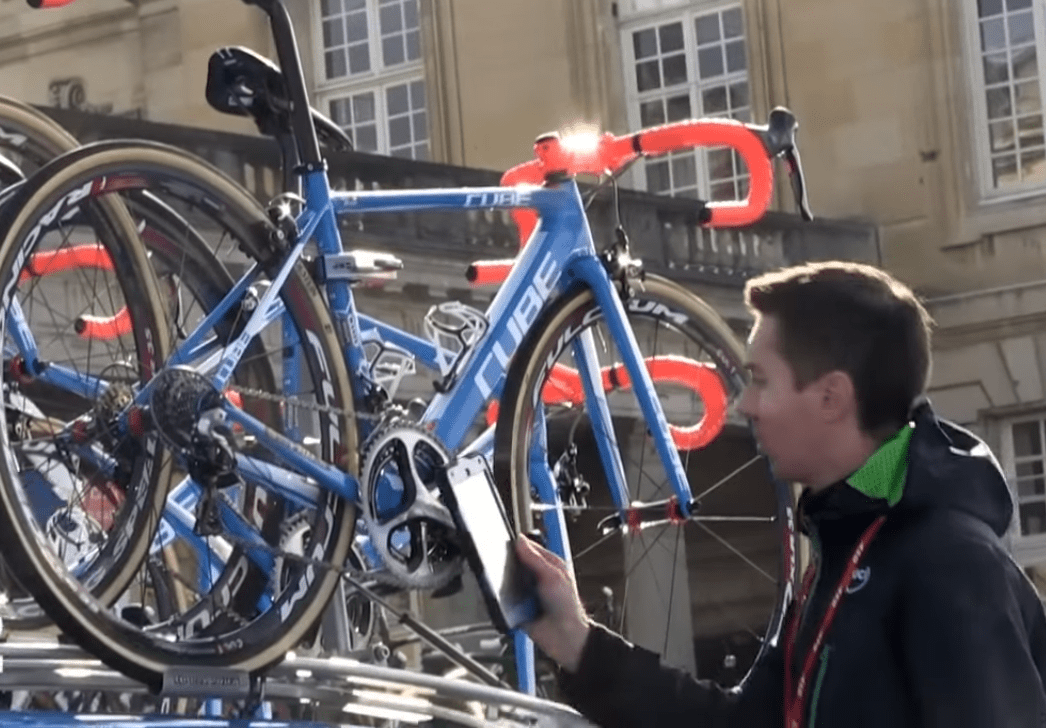

Testing for motors came into focus as the UCI succumbed to public pressure, leading race commissaires to thoroughly inspect the bicycles of Hesjedal’s Garmin–Sharp team the following day. Despite the scrutiny, no motors were found. Subsequently, in the following spring, bike motor inspections became a regular practice at prestigious events such as Paris–Nice, Milan–San Remo, and the Giro d’Italia, using tablets.

The French and Italian exposés in 2016

In 2016, the French television show Stade 2 asserted that the prevalence of mechanical doping was potentially higher than previously thought, and it was going unnoticed by the UCI. Conducting an investigation with a costly thermal camera cleverly disguised as a standard video camera, the program recorded footage during the Strade Bianche and the Coppi e Bartali stage race. In a 20-minute segment, the show presented a persuasive argument, suggesting that they had indeed captured evidence of mechanized doping.

According to a report in the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera in the same year, the television program identified seven instances of mechanized doping using the thermal camera. In five cases, heat in the bottom bracket was detected, suggesting a motor assisting the crank. In two other instances, heightened heat was observed in the rear-wheel’s hub or cassette. Consulting a thermal imagery specialist, the program received confirmation that the captured images were suspicious. The footage indicates an abnormal amount of heat in bike areas that shouldn’t generate heat.

There has been speculation over the years that Lance Armstrong might have used a motor in his bike. Observers noted his habit of tugging at the back of his shorts during races. That prompted some to wonder if he was activating a hidden mechanism. Armstrong vehemently denied any involvement in motor doping, stating in a Cycling Weekly article, “In 1999, no one even knew you could put a motor in a bike.” The former pro cyclist explained that at the time he would adjust his shorts such that the chamois was centred on his saddle. He believed it would help his pedalling efficiency.

The Sepp Kuss accusation

In September, former pro Jérôme Pineau spoke out about American Sepp Kuss’s attack on the Tourmalet during the 2023 Vuelta a España: “The international bodies are destroying cycling. They let too many things happen, don’t control anything anymore and do what the big teams want. That is the big danger. So then you can start thinking what you want,” he begins. “We see the pictures…I am not talking about doping, but about something that is even worse.”

“Mechanical doping? Yes, mechanical,” he continued. “If you watch Sepp Kuss’s attack on the Col du Tourmalet, against riders like Juan Ayuso, Cian Uijtdebroeks–-who is a great talent–-and Marc Soler. They’re not so slow on bikes, are they? Kuss rides ten kilometres per hour faster with his attack, then has to slow down because of a spectator and then rides ten kilometres per hour faster after.”

A few days after the accusation, Kuss said that he was completely against any sort of doping, whether by PED or motor. “I think for me personally, cheating or doping is just out of the question. Because it’s not even sports for me then,” Kuss said to GCN. “Part of sports is losing. Of course you want to win, but if you’re doing something that’s prohibited or cheating, then you’re afraid of losing, which I think is one of the most important things about sports: accepting that sometimes you’re not good enough. That’s just how it is.”

The 2016 cyclocross worlds

Belgian Femke Van den Driessche was caught utilizing motor doping. During the 2016 ‘cross worlds, the UCI discovered a motor in one of her spare bikes. She claimed it was a friend’s bike mistakenly placed there and denied any intention to cheat. “That bike belongs to a friend of mine. He trains with us. He joined my brothers and my father. That friend joined my brother at the reconnaissance, and he placed the bike against the truck, but it’s identical to mine,” she said. Last year he bought it from me. My mechanic cleaned the bike and put it in the truck. They must’ve thought that it was my bike. I don’t know how it happened.”

At the time, by the way, her brother Niels was currently serving a suspension for doping.(He and their father were also accused of stealing expensive parakeets, but that’s a whole other story.)

The pre-testing period

This incident resulted in increased vigilance and regular checks. According to the podcast “Ghost in the Machine,” which focuses on technological fraud, and more specifically, Van den Driessche, there was not a rigorous testing protocol in place for several years prior to this.

Brian Cookson was the former president of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), serving from 2013 to 2017.

Motor doping may have happened at UCI WorldTour competitions before 2014: official

Toward the end of his tenure, the issue of motor doping gained prominence. The UCI took measures to address the concerns related to technological fraud in cycling. Brian Cookson, as the head of the UCI, emphasized the importance of tackling motor doping and implementing measures to ensure fair play in the sport. The UCI introduced various technological methods and protocols to detect the presence of hidden motors in bicycles, including thermal imaging and magnetic resonance testing.

Questioning the robustness of the testing

Despite the UCI’s assertions of implementing comprehensive mechanical doping tests at all UCI WorldTour and UCI Women’s WorldTour events, a September investigation by the RadioCycling podcast exposed significant inconsistencies and deficiencies in these efforts. A crucial finding from the report reveals the omission of technological fraud tests during four out of the 21 stages of the recent Giro d’Italia, including the critical time trials on Stages 1 and 10.

Equally alarming was the absence of the essential X-ray technology designed for detecting mechanical doping during the opening Grand Tour of the 2023 season. The Tour de France also lacked X-ray tests on Stage 21 in Paris. These lapses were not confined to the Grand Tours alone but extend to other competitions. That included the Volta a Catalunya, the Tour of Scandinavia, and the Tour Down Under. Another concerning aspect highlighted in the investigation is the lack of data sharing. Paris-Nice witnessed the absence of testing on stages 5, 7, and 8, while Milan-San Remo and significant women’s races such as Paris-Roubaix and Flèche Wallonne experienced limited controls due to inadequate testing measures.

UCI still skeptical about usage

In light of these deficiencies, senior UCI officials expressed skepticism about the potential presence of concealed motors within the peloton, raising questions about the credibility of professional cycling. In an attempt to address these concerns, RadioCycling gathered data from 51 men’s and women’s WorldTour races. Surprisingly, only 24 races provided data, 12 confirmed that the UCI had not disclosed any statistics. 15 remained unresponsive.

The UCI defended its program against technological fraud in a statement to RadioCycling: “The UCI’s program against technological fraud has developed steadily over the years and provides a robust system for the detection of any possible propulsion systems hidden within framesets or other bike components,” it read. “In 2023, a total of 4,280 controls were performed. Magnetic tablets were used for 3,777 of the controls and X-ray technology. All tests were negative.”

There have been plenty of cases of amateurs being accused or caught for this form of cheating, it should be noted. And there have been suggestions by Italian media that if any form of motor doping exists, it is not necessarily with a motor in the down tube, but could be using ectromagnetic wheels.

Former Tour de France winner Greg LeMond has often spoken out about his views about motor doping, saying in road.cc in 2017, “I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France.”

2021 allegations about motor doping using wheels

In 2021, an article published in Le Temps suggested some riders had heard “strange noises” coming the bikes of four teams. They: Team UAE-Emirates, Deceuninck-QuickStep, Jumbo-Visma and Bahrain Victorious.

When yellow jersey Tadej Pogačar was asked, he was shocked at the question.

“I don’t know. We don’t hear any noise. in disbelief at what he was being asked. “We don’t use anything illegal. It’s all Campagnolo materials, Bora,” he said. “I don’t know what to say.”

The article said that one of the riders believed the noise was coming from the rear wheels. “A strange metallic noise. Like an incorrectly adjusted chain,” the unnamed cyclist said. I’ve never heard it anywhere.”

“We are no longer talking about a motor in the crankset or an electromagnet system in the rims of the wheels, but a device hidden in the hub,” another unnamed source said. “We are also talking about a recuperator of the wheels. Energy is sent via the brakes. Inertia is stored just as in Formula 1.”

However, to this date, only Van den Driessche has ever been caught for technological fraud.